What is the personal and social impact of a violent layoff? The Ssangyong Motor Company incident in 2009 in which the labor union protested the layoff of 36% of its employees was laden with symbolism. The sit-in by workers and family members at the Pyeongtaek automotive plant quickly escalated into violence as company-hired thugs instigated physical confrontations and the police cut off all water, electricity, gas, and outside contact. Armed with tear gas and taser guns, the police stormed the factory roof to force out the protestors and their makeshift slingshots. The media overwhelmingly blamed the incident on the ”violent and unreasonable labor union”.

While the 77-day protest ended on August 6, 2009, the violence continued with subsequent strikes and deaths by illness and suicide by former employees and family members. Gradual subsequent negotiations and step-wise rehiring left a final group of 119 workers. Of these, 71 were reinstated by December 2018, and the rest are set be rehired in early 2019. Behind the scenes, meanwhile, the facts are finally surfacing through media and government investigations into company mismanagement and heavy-handed government suppression.

This November 2018 article reflects on the decade from the perspectives of the often-forgotten spouses of the laid-off workers. The trauma not only ravaged the workers and their family members financially, but also cut them off from their communities, resulting in a high incidence of depression and suicidal ideation. How they cope and survive through the trauma is partly our responsibility. The researcher who surveyed the spouses leaves us with a warning: “Employment instability and layoffs will not be variables but constants in Korean society. We may have been thinking that what the laid-off SsangYong workers and their families suffered was just someone else’s pain, but it is something that we may all experience at some point.”

— RHL

On September 13, 2018, the trade union and management at SsangYong Motor reached an agreement to reinstate each of the 119 workers who had yet to return to the factory after the layoffs of 2009. It took ten years. The trade union and management have decided to reinstate 60 percent of the 119 workers by the end of 2018 and the rest by the first half of 2019. They even announced a detailed schedule to complete the reinstatement of workers by the second half of 2019 at the latest. Moon Sung-hyun, former labor activist and chairman of the Economic, Social and Labor Council, a presidential advisory body, was unable to hold back tears as he announced the deal at a press conference on September 14. Chairman Moon stated, “Although the laid-off (SsangYong Motor) workers have suffered due to the bondage as laborers, I would like to express my gratitude here today, on behalf of the government, to the family members who have guarded their families for ten years. Hang in there, family members. We wish you warm hearts this Chuseok.” Chairman Moon broke into tears as he mentioned the “bondage” of laborers. For a long time, the layoff has yoked the bodies and souls of the SsangYong workers. A highly contagious bondage of despair has also choked the spouses who had to watch their husbands suffer. Around the time the reinstatement deal was being finalized, a research team led by Professor Kim Seung-sup of Korea University’s School of Health Policy and Management, who has for many years studied the health conditions of SsangYong’s laid-off workers, released the results of a study on the health conditions of their spouses. — Meconomynews

Meconomynews

On September 6, a week before the reinstatement agreement, the results of an April 2018 study titled “Can You and Your Family Accept This Type of Layoff?” were presented at the Franciscan Education Center in Jeong-dong, Seoul. Led by Professor Seung-sup Kim of Korea University’s School of Health Policy and Management and run in conjunction with the National Human Rights Commission of Korea and Warak, a psychological treatment center for the laid-off SsangYong workers, the study focused on the health conditions of both the laid-off workers (including reinstated workers) and their spouses. The worker survey was conducted in April and May 2018 and the spouse survey in June 2018 (from June 5 to June 29).

There have been several studies on laid-off workers since SsangYong’s massive layoffs in 2009, but this was the first to include the spouses. Conducting the study was no easy task. “It is, in fact, painful for the subjects to recall and retrieve the memories from that time, and many experienced new pain as they had to talk about the memories that they had suppressed and as the emotions that they did not wish to remember returned,” said Kwon Ji-young, President of Warak, and wife of a reinstated worker.

One of the words Professor Kim used most frequently during the presentation was “anguish”. Professor Kim said spouses of the laid-off workers participated in the survey as “a way to express their anguish”. Their husbands were laid off a decade ago, but the scars and trauma from that time still remain significant to them even today. These scars and trauma never go away. “Despite the scars and trauma, life goes on,” said Lee Sang-yoon, head of the Association of Physicians for Humanism. “But unlike how people often think, the scars and trauma don’t disappear. They can unexpectedly resurface throughout your life like cutaway shots in films, and that’s when you get teary and depressed for no reason.”

Professor Kim stressed that this research is nevertheless essential for our society. “The reason why we press the participants to talk about their distressful experiences and quantify such experiences into numbers is that we need to look at the impact of the layoffs on Korean society through the families of the laid-off SsangYong workers and to look at the world through the lens of the laid-off workers and their families, not through the lens of the companies that are laying people off for managerial reasons,” said Professor Kim. “If we don’t do this, then the pain suffered by the laid-off SsangYong workers and their families will be repeated in different places at different times.”

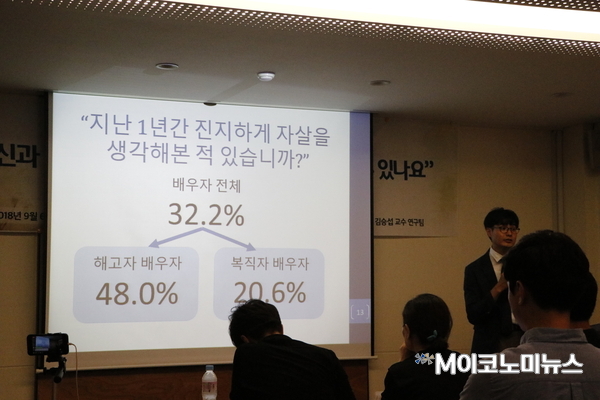

Professor Kim Seung-sup of Korea University announces the results of the study at the Franciscan Education Center in Jung-gu, Seoul, on September 6 | Meconomynews

Suicide and depression… Shocking numbers

The study results were just as grave as the distressful memories shared by the subjects. When asked if they have ever “seriously contemplated suicide in the past year”, 32.2% of the spouses who participated in the study (28 spouses of laid-off workers and 38 spouses of reinstated workers) responded “yes”. Among those who have contemplated suicide, 48% were the spouses of laid-off workers and 20.6% percent were the spouses of reinstated workers. Professor Kim said, “The numbers were shocking.” We need to understand the depth of the numbers rather than their size.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey conducted by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the prevalence of suicidal ideation among women in the same age group as the spouses of laid-off or reinstated SsangYong workers over the past year was 5.7 percent. The number of spouses of laid-off workers who have contemplated suicide was 8.67 times higher; the number of spouses of reinstated workers was 3.72 times higher. There is another thing to consider. Korea already has the highest suicide rate among the OECD countries.

It is not an exaggeration to call these numbers shocking, even in comparison to a July 2018 study by Professor Kim on the survivors of the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan. Performed in conjunction with Hankyoreh and Hankyoreh 21, that study revealed that 50% of the surviving soldiers had “contemplated suicide over the past year”.

The spouses also considered themselves to be in poor health. 42.3% of the spouses of laid-off workers and 17.1% of the spouses of reinstated workers thought their health was poor. When the spouses of the reinstated workers were compared with control women of the same age group, there was no big difference: these spouses were 0.9 times less likely to say their were in poor health. But the number for spouses of laid-off workers was 2.23 times higher. Furthermore, 82.6% of the spouses of laid-off workers and 48.4% of the spouses of reinstated workers suffered from depression. These percentages were, respectively, 8.27 and 5.27 times higher than for control women who were asked the same question.

The layoff of their husbands isolated the spouses from social relationships. While it was the husbands who were laid off, 70% of the spouses of those husbands responded that they felt alienated. In addition, 45% of the respondents stated that they felt that they did not fit in and felt uncomfortable around other people. In Korean society, being laid-off not only served as a simple economic difficulty but also as a social stigma, resulting in isolation and disconnection of the laid-off workers themselves and also their family members.

They placed themselves under the bondage on their own. When someone is isolated and disconnected from social relationships, they first turn to their family members. However, this was not an easy option for the spouses. When asked how satisfied they were with their husbands, 33 percent of the spouses of the laid-off workers and 18 percent of the spouses of the reinstated workers were dissatisfied. These numbers were 3.85 times and 1.86 times higher compared to other women in the same age group.

Former Chairman of SsangYong Family Relief Committee Lee Jung-ah (left) and Executive Secretary of SsangYong Chapter Kim Jeong-wook (right) | Meconomynews

Just because they were married to laid-off SsangYong workers

According to Professor Kim, the spouses were discriminated against because their husbands were laid-off SsangYong workers. 54% of the spouses of the laid-off workers and 62%of the spouses of the reinstated workers responded that they had “experienced discrimination” since 2009. Discrimination took place in their ordinary lives. The spouses responded that they experienced discrimination at work the most (66.7%), followed by on the streets or in their neighborhoods (33.3%) and in stores and restaurants (30%). Professor Kim explained, “Discrimination refers to insulting incidents experienced by the spouses on the streets or in their neighborhood. [The strike] was a fight that stirred up the entire Pyeongtaek area, and the stigma attached to the laid-off workers also extended to their wives and family members.”

Other spouses cut themselves off from others on their own volition. A wife of a laid-off worker said,“I heard of one lady sharing that her husband had been laid off by SsangYong, only for a colleague to say behind her back that the laid-off workers were selfish and to blame.” When the strike had just ended (in 2009), there was still a lot of tension in the community, so I felt like people were criticizing and condemning us and our family members.” In another case, a laid-off worker who was placed under arrest was taken to a hospital due to health problems during interrogations, and the hospital happened to be the one where his wife was working. The wife had to face her husband, who was handcuffed and escorted by the police, in front of her colleagues.

A wife of another laid-off worker testified, “Pyeongtaek is a very small town. For most laid-off workers, it is their hometown and where they went to elementary school, middle school, and high school, where they went to work at SsangYong, and where they were laid off. Since everyone knows everyone else, people know who the laid-off workers are and whose husbands they are.” She then said, “The laid-off workers and the family members were forced to withdraw through these experiences even without others pointing fingers at them or saying they were bad people to their faces.”

Ten years as mothers and as women

While the study quantified the pain experienced by the wives of the laid-off SsangYong workers, the press conference provided an opportunity for the people to hear their experiences of having to endure the pain as mothers and as women in Korean society. “I’ve had countless interviews and talked about many things over the last ten years, but questions about my children still haunt me,” said Lee Jung-ah, former Head of SsangYong’s Family Relief Committee. Lee’s husband returned to the factory in April 2017.

“It was difficult to remain seated during a media interview because I was crying as old memories started to come back. I feel puzzled stares as to our difficulties in participating in interviews because it’s already been over a year, our husbands were reinstated, and our children grew up healthy,” said Lee. “I’m fine. We can always testify in front of the prosecutors, the police and the media until the rest of the laid-off workers return to work. But when these stories get circulated and told to my children through their friends and school teachers, I wonder how those stories will hit them on the inside, and that’s what makes it difficult,” sobbed Lee. She grabbed the microphone bravely, but she ultimately shed tears as she talked about her children. She cried for her children, because the parents’ pain gets passed on straight to their children.

“A four-year-old child who had accompanied his mother and father to the factory during the (2009) lockout strike could not ride a bus and would convulse at the sound of helicopters for several years after the strike. The little kids from ten years ago are now teenagers, but some have never talked about their fathers’ work and others only asked about the company after their fathers were reinstated,” said Yoo Geum-bun, a counselor at Warak Healing Foundation. “It’s an insurmountable scar, one that will not heal until the day they die.” She emphasized, “It is too much to leave it up to the individuals to deal with their scars. It is absolutely necessary to establish a safety system to deal with the never-ending layoff issues. We need to work together to build a social safety net.”

Korean women’s issues exposed

The pain inflicted on wives of laid-off workers also laid bare the problems of women in Korean society. They were forced to play a certain role and had to endure it because they were women. “The laid-off workers bear the brunt of the shock, pain and suffering, said a wife of a laid-off worker at the press conference. “There is no argument about that. But, since it is difficult for the laid-off workers to recover from the shock and they start to sink into themselves, the duty to earn a living for the family, to care for the children, and to spend emotional energy on dealing with the worries and consolation from elderly parents falls on the wives.”

“The emotional burden of having to care for the elderly parents of both families and relatives is mostly on the spouses (wives),” she continued. “The spouses had to handle all that by themselves, just as the women in Korean society were always being asked to play the same gender role. (At the time of the strike), we should have shared the burden with our husbands, but we thought we should bear it all ourselves, thinking, ‘how hard it must be for our husbands’ and tried to stay strong. Now, when we are faced with an event that causes harm, we need to focus on the weakest and those suffering the most. For us, that was our children, which is why we have created and maintained an organization like Warak.” She added, “Let’s turn our eyes to those who are at the bottom of the society. When the most vulnerable people become happy, our society will become a happy one without additional efforts.”

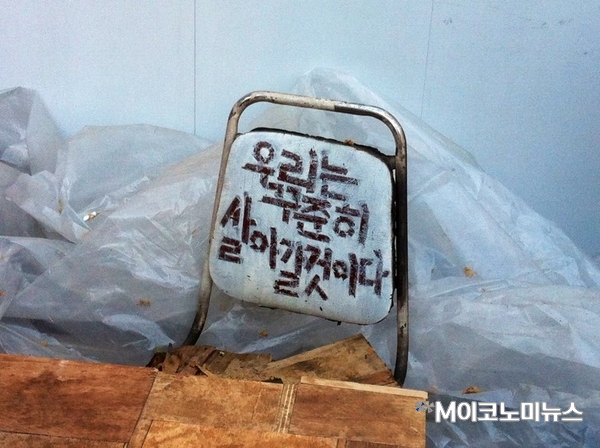

A chair with the phrase ‘We will keep on living on’ remains after a fire broke out during the SsangYong sit-in demonstration in March 2013 at Daehanmoon, Jung-gu, Seoul. | Meconomynews

We will keep living on

“The Korean society is indebted to the laid-off SsangYong workers,” said Professor Kim Seung-seop during the presentation of the study. When average people are laid off, they drift apart because they are reminded of the painful experience every time they run into each other, and it is difficult to have hope in reinstatement. But the laid-off SsangYong workers endured the past ten years, crying out “let’s survive together”. “Because they stayed together, we had the chance to ask them about their experiences of the past ten years,” said Professor Kim.

“I think these stories are the only data that have concrete implications for the laid-off workers and their families,” said Professor Kim. “As I was preparing for today’s presentation, I was worried about the laid-off workers. Every time an article appears on the Internet about the sufferings of the laid-off workers, people post comments, and most are derisive or insulting to the laid-off workers,” said Professor Kim. He further explained, “When we try our best to understand these comments, we can say that that they stem from the anger and difficulties experienced by young people, who live as temporary workers or are unemployed in a society where it is difficult to find a good job.”

“I want to talk about three things. First, the laid-off SsangYong workers are not demanding something much. They are asking to return to the factory because they were unfairly dismissed. It is a reasonable request. Second, the authority and society that have created the structure that led the unemployed young people to criticize the workers who have been laid off for nine years are becoming more powerful. Third, it won’t beeasy for anyone in Korean society to mass produce decent jobs over the next few decades. Employment instability and layoffs will not be variables but constants in Korean society. We may have been thinking that what the laid-off SsangYong workers and their families suffered was just someone else’s pain, but it is something that we may all experience at some point. The same future could await any of us,” said Professor Kim.

Our society needs to embrace ten years of scars and trauma

In March 2013, a tent at the SsangYong workers’ sit-in demonstration site in front of Daehanmun in Seoul was set ablaze. One chair that survived the fire had a wish of the laid-off workers written on it: “We will keep on living on”. (From the poem of the same name by Lee Myeon-woo. A sentence in the poem reads, “We who have not been worn down from life will keep on living on”). To sit in a chair means having a position, and for the laid-off workers, this must have meant reinstatement. The laid-off SsangYong workers and their families gathered together even in times of despair. They fought and survived, and as they had hoped, they came to an agreement with the company for reinstatement. They will continue to live on. However, the scars and trauma from the layoffs from ten years ago still remain. It is our society’s role to embrace them.

This article comes to you in partnership with Meconomynews. It was originally published on November 2, 2018. Have feedback for the writer? Send us a mail or sign up for the newsletter.