Have a question for this writer? Send him a mail or sign up for the weekly newsletter.

On December 4, 2017, The Atlantic presented an unusual article for the US web, introducing the Korean news industry. It described the relationship between the media industry and Naver, the leading portal site in Korea, and the tensions of recent years.

The piece did a good job presenting the digital media environment of Korea, a rare and unique set of circumstances when compared with the rest of the world. However, it lacked certain details on how the news services at Naver and Daum (its main competitor) actually function. I’d like to focus on these two portals, and introduce them in more depth.

A brief history

Naver started Naver News in May 2000, allowing its users to search the content of 15 news outlets. At launch, the service lacked any concept of news curation—an approach that is now standard among Korean portals, and referred to locally as ‘editing’. In this respect, Naver was behind Yahoo! Korea, the biggest portal at the time.

Then, however, Naver followed Yahoo! Korea’s model. It set up a news service team and started providing ‘edited’ news on the front page in September 2001. In December 2002, they recruited Choi Hwi-young, who had been heading Yahoo! Korea News.

In March 2003, another portal, Daum, launched a news service under the brand name Media Daum[1]. They immediately sourced content from 20 news outlets and provided it to users.[2]

The reason why I’ve droned on about the origins of the Naver and Daum news services is to help you see a picture of the contract relationship between Korean portals and news media. The news services on Korean portals are very different from, say, Google News. While that portal likewise provides search results and trending topics, Google does not pay out or receive money. Naver and Daum, on the other hand, purchase content from media companies and provide it to readers (after ‘editing’).

What Korean readers see (spoiler: everything)

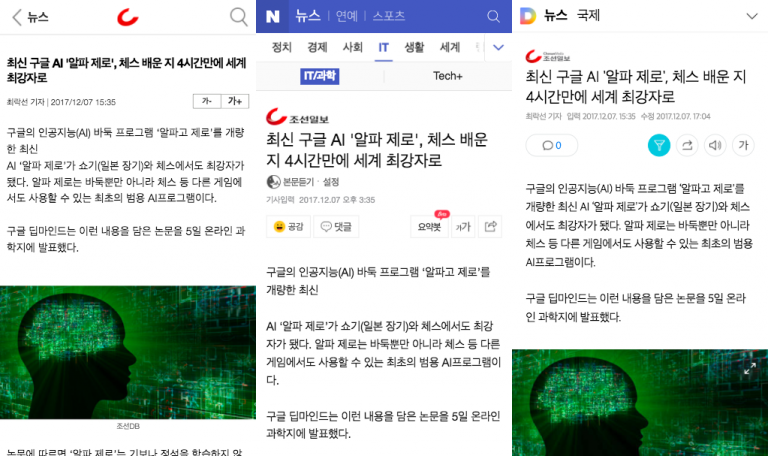

Both Naver and Daum outsource articles from media companies in real time. The portals then store the articles on their databases and present all of them on their websites. So, when a reporter of Chosun Ilbo, the largest newspaper company in Korea, writes and posts and article, the same piece can be seen on ‘chosun.com’, ‘news.naver.com’ and ‘media.daum.net’.

The same article on chosun.com, news.naver.com, and media.daum.net.

This holds for every other newspaper and broadcasting company in contract. To paint a better picture, imagine this: being able to read almost every important news article in real time from USA Today, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post, CBS, NBC, ABC, Fox News Channel, USA Network, and AP News—all on one website, in one standardized layout. For free.

News content provided by Hankook Ilbo, Newsis, and Inews24 on Naver News.

Portals vs Media

There are mainly two types of contracts between portals and media companies. The first is what we’ve seen above, through which a media company sells content to a portal, for use on the portal’s news service. The second type is for search results. When a media company and a portal agree to this, articles from the media company become searchable on the portal. So the agreements make it possible to read (type 1) or search (type 2) the articles on a portal. Partners on the first type of contract are called “in-link partners”; those on the second, “search partners”.

Of course, this rather peculiar set of relationships hasn’t been like this from the start. It has been reached through a long period of collaboration and arguments between Naver, Daum, Yahoo! Korea, other now-disappeared portals, and a number of key media companies.

Anyway, in around 2005 it became indisputable that portals were the primary channels for news consumption in Korea. People read news on portals and searched news on portals. When a media company launched, one of its first missions was to establish partnerships with portals; if it didn’t, people would never discover its content. Once any type of partnership was established, the media site traffic was expected to soar.

‘News abusing’ and the fight for quality

Tensions and conflicts ensued, between two groups: media companies, media academia, civic groups, politicians on one broad team, and portal operators on the other. We can find numerous articles illustrating the controversies, such as Portals Should Realize Their Social Responsibility in 2005, Politics Trying to Tame Portals in 2006, E-Power, Portals: Media Out of Control in 2007, and Algorithmic Recommendations” vs “Regulation Needed” Portal News Debate in 2017.

In September 2017, Korea Press Foundation released a meticulous research paper illustrating the conflicts surrounding portal news services.[3] The foundation posited six fronts on which media allies and portals fight: contract fees, innovation, advertorials, responsibility for the decline in journalism quality, ‘news abusing’, and the Committee for the Evaluation of News Partnership. I’ll focus here on the final three.

1) On the aspect of journalism quality, media companies argue that the domination of news distribution by portals has devastated the media environment and diminished journalism. They claim that, in luring news producers into clickbait wars for visitors and traffic, portals have caused a vicious cycle in which media companies fail to secure profits to invest in high quality content.

2) Following on from the quality matter, there arises the most peculiar and unique media problem of Korea: ‘news abusing’. Such abuse is defined as duplicating articles in order to increase their frequency in search results and, thereby, earn clicks.[4]

On December 5, 2015, an entertainment outlet alleged that a famous foreign chef in Korea had forged his qualifications. Two days later, it turned out that the report was not true and the outlet posted a correction article.

The story of a popular chef’s career forgery must have been attractive. From December 5 to 7, 231 articles were published containing almost identical structures and words. When a user searched for the chef’s name, they saw something like this:

Naver.com search results for the term ‘미카엘’, the chef’s name in Korean. Each of these articles were published by the same news outlet | MediaToday

Two arguments coexist. With the rapid changes in the advertising market and media environment, media companies are finding it difficult to generate revenue from traditional business models and are forced into “news abusing” in order to earn traffic. On the other hand, some observers point to how changes to portal news services have contributed to the problem of abuse. Indeed, many are calling for portals to be held responsible too.

3) After a decade of conflict and debate on the responsibility issues mentioned above and questions over the right of portals to manage partnerships, in 2015, Naver and Kakao (the operator of both Daum and the country’s single dominant messaging service, KakaoTalk) agreed to establish an independent committee, the Committee for the Evaluation of News Partnership. The Atlantic described it this way:

The committee has two key functions. The first is to evaluate which new outlets can supply news to portal sites. The second is to penalize news outlets that violate contract conditions, such as publishing sponsored or violent content, or clickbait.

Put another way : the committee decides not only which media companies can make contracts with portal sites, but also which should be expelled from portal news services or search results. The 30 committee members are appointed by 15 organizations such as the Korea Broadcasting Association, the Korea Newspaper Association, and the Korea Press Foundation.

However, as with oversight committees in any country, the existence of one does not guarantee all problems solved. This is why the Korea Press Foundation includes this committee on its list of six battle fronts. In its paper, the foundation details both the criticism over portals being allowed to delegate their responsibilities to another organization, and the doubts over the ability of a committee comprising direct stakeholders to make a fair evaluation that all media companies can accept.[5]

AI is here

Naver and Daum have maintained market dominance in spite of the controversies. And they have improved on quality with the help of technology superior to that of traditional media companies.

The services employ a variety of technologies, but all eyes are now on artificial intelligence. AI has the potential to decide both which articles to show and the sequence of those articles on the front page.

In this regard, Daum was the fast mover. In June 2015, the portal implemented RUBICS—Real-Time User Behavior Interactive Content Recommender System—on its front page. Kakao, the operator of Daum, briefly explained how it works on its official blog:

1) Cluster analysis 2) Redundancy/abusing Filtering 3) Articles against the service principles are excluded. After that, RUBICS automatically arranges the article on the front page.

Kakao revealed that RUBICS was built primarily on the Multi-Armed Bandit algorithm, and that they tweaked MAB to make it suitable for news recommendation.

Naver’s AI arrived in 2017. They named it AiRS, short for AI Recommender System, and based it on two principal technologies: CF (Collaborative Filtering, Cooperative Filter) and RNN (Recurrent Neuro Network). CF recommends certain types of content to readers with similar interests by analyzing content consumption patterns.

Two lawmakers recently held a debate to question the fairness of portal news services, with Naver and Kakao’s media representatives in attendance. Both representatives put AI forward as a solution to the fairness challenges. Remember the news article I mentioned that covered the tension between portals and news media companies?

“Algorithmic Recommendations” vs “Regulation Needed” Portal News Debate, 7 Dec 2017, Min Hye-jeong.

“Currently, 20% of articles on the front page are curated by [Naver editors],” said Yoo Bong-seok, Naver Media and Knowledge Information Leader. “Going forward, all curation will be done by external experts and algorithms.”

Lee Byung-sun, vice president of Kakao, said “Kakao’s news services are mostly based on RUBICS, and mobilize human editing only for breaking news that everyone needs to know, such as earthquakes.”

Portal dominance, in one chart

The reason why portals have been constantly criticized by media companies, media academia, civic groups, and politicians alike is simple: portals are surprisingly powerful.

Most Koreans need no assistance in recognizing this dominance. Let’s say you are on a bus in Seoul. Look at a smartphone held by someone near you: unless they are messaging or enjoying non-news content like video, what you will be looking at is news presented by a portal.

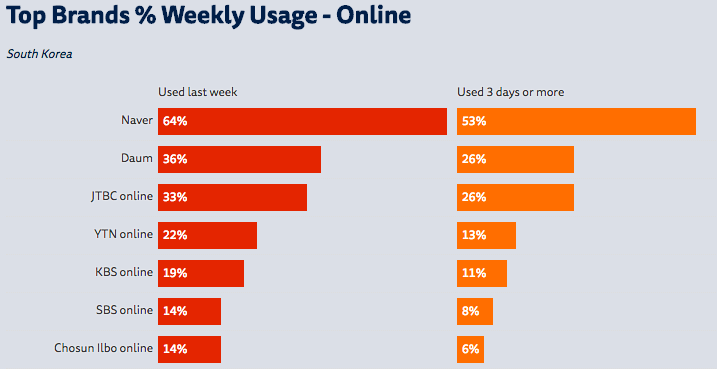

For those who do not live in Korea, the Reuters Institute puts out helpful statistics. Let’s look at the South Korea chapter in their most recent Digital News Report.

Portal sites such as Naver (64%) and Daum (36%) are the most popular news outlets in South Korea, eclipsing the websites of newspapers and broadcasters as well as social networks like Facebook (28%).

And here’s an interesting detail from the Korean edition that wasn’t in the English.

When consuming digital news, 4% of Koreans answered that they mainly visit media websites [not portals]. This figure is significantly lower than that of Japan (16%) or France (21%). The countries with high reliance on media websites were Finland (64%), Norway (62%), the United Kingdom (58%), Sweden (52%), and Denmark (50%).

Just a peek

A snapshot article like this cannot fully explain the complexity of the Korean news business—intertwined as it is with technology, media, politics, and citizens. Technology companies are doing their best, in their own ways, but face constant criticism; media outlets produce content but aren’t satisfied with the conditions; politicians wish to tame the dominant news services but don’t know where to begin; and citizens feel something is wrong but don’t ask for change.

But I hope this helped you draw a picture of what is going on here in Korea, when it comes to news consumption. I’ll say more soon.