The sixth in an award-winning series of interviews with Korean theater professionals, first published in The Dong-A Ilbo.

First, I asked if there were many people who served as both playwright and theater critic. She named two or three, none of whom rang a bell. Seeing the expression on my face, she blurted out that Brecht had. It wasn’t that she was comparing herself to Brecht, just trying to emphasize that there really are people who do both jobs.

There is a reason for her defensiveness. The theater community is quite critical of anyone who both writes and critiques. They say that it is a “contradiction” for someone to have both a spear and a shield. On the other hand people are relatively generous about playwrights who also direct, because both tasks are considered “creative”. Some even say that plays become boring when playwrights study play writing.

“There was a point in time when people weren’t comfortable with playwrights who also critique plays, but the times have changed. Boundaries between playwriting, directing, acting, and critiquing have lowered, and people even cross genres these days. It’s the same in other countries. Patrice Pavis, a famous French professor in Theater Studies said, “People in theater don’t like critics who write works, but they still write in secret.”

She doesn’t write in secret.

As for the reason:

“A lot of people told me that if I write plays and also critique them people will criticize my plays and that things might not work out so well. I think that’s true. But shouldn’t you go down the path you want to go down?

It was a rather philosophical take on her situation.

What does it mean that a lot of unqualified theater critics have emerged since the 1990s?

“There aren’t many ways to debut as a theater critic. I think it’s because people who studied theater or plays just started writing, and came to be called theater critics that way, naturally.”

The International Association of Theater Critics-Korea introduced itself as an organization with over 80 members in the book titled Korean Theater Since the Sewol Ferry published in June 2017. The standards were ambiguous, but it seems that less than half of the people on the list are active in the field. It’s because there are too few places for theater critics to fulfill their desires, be that in daily newspapers, weekly magazines, monthly periodicals, or theater-specific journals.

Since she was writing and critiquing plays, I asked if she ever thought about directing. I only asked it thinking that she’d say it was unthinkable.

But I was wrong.

“Originally directing was what I wanted to do. I worked as an assistant director under Kim Seok-man. It was hard because he was very authoritative. I thought that I needed to be really strong and tough to direct. And I’d directed with the help of an upperclassman when I was an undergrad.”

She is currently preparing to go into directing. Writing, directing, and critiquing all by herself. Sounds like a new paradigm is on its way.

It is true that people have criticized her for being both a playwright and critic, but it is difficult to object to the fact that she proved herself in both playwriting and theater criticism. Who is this “she”? She is the quiet but extremely ambitious Kim Myung-Wha. I met her at the Dong-A Ilbo offices on August 10, 2017. (I didn’t interview any other critics for this series. So I asked for her understanding in focusing more on criticism than playwriting.)

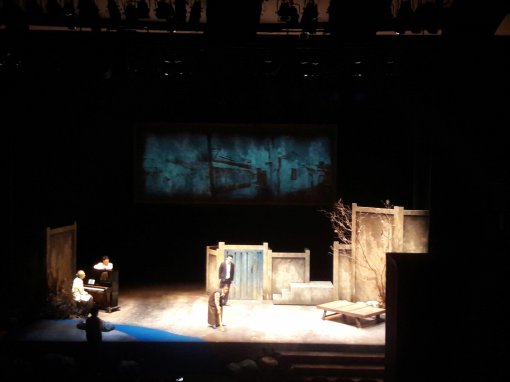

First Birthday (Dolnal)was the play that solidified Kim Myung-Wha’s position as a playwright. After its premiere in 2001, it was put on stage several times including in 2011. Friends gather together at the first birthday celebration for the second daughter of Ji-ho and Jeong-sook, two people of the 386 generation married to each other. Where have their brilliant dreams and ideals disappeared to? Is this what people mean when they say that they are laughing but actually crying on the inside? Kim asks these questions objectively, but the audience’s hearts ache | Theater Company Jageun Shinhwa

1. The path of this theater professional began in theater criticism

Kim made her debut as a theater critic when she received the Ye-Eum Award in theater criticism from the Ye-Eum Foundation in 1994. She officially became critic through this narrow opening.

Immediately afterward, she began to write for a monthly magazine (Auditorium), and then for a weekly paper (News Plus) a year later. It was interesting, because it was rare for magazines to give a regular writing gig to a newbie.

“The Korean Theater Review recommended that I write critiques in 1992. I had some time to be trained.”

Kim graduated with a degree in educational psychology from the teachers’ college at Ewha Womans University in 1998. She received a master’s degree in Theater and Film at Chung-Ang University with a thesis on ‘Erwin Piscator’s Stage Techniques’ in 1992, and a doctorate from the same university in 2000 with A Study of Oh Tae-seok’s Play Space. Come to think of it, she wrote a lot of relatively short reviews in monthly, weekly, and daily papers prior to receiving her doctorate, but she published longer critiques in The Korean Theater Journal and The Korean Theater Review after receiving her doctorate. In 2006, she put all her reviews and critiques together and published Kim Myung-Wha’s Theater Reviews—The Curtain Goes Up At 7:30 pm and Kim Myung-Wha’s Theater Critiques—The Path to Theater, the Path to the World (both from Theater and Man Press). In the former, there are 181 reviews, while the latter contains 21 critiques. She also published a collection of plays titled Cafe Shinpa.

Kim has a firm stance on theater criticism.

“Theater criticism is important because, unlike literature or fine art, which last forever, performances are a one-time thing. Theater criticism is the only lasting evidence for performances, which otherwise disappear once a play is over. It is also the only validation of a performance’s value. Therefore if a critique misreads a performance, there is absolutely no way for that particular critique to be overturned later in history, unlike for other arts.” (From Modern Theater and Theater Criticism, a lecture at a 2000 Spring workshop on expression and imagination, quoted from The Path to Theater, the Path to the World.)

She said the same thing several times in papers and roundtable discussions. In my own words, it seems that she is saying, “It is not what exists that becomes documented, but what is documented that exists. Therefore it is important to document.”

I found several characteristics, or personalities, in both her reviews and her critiques. Like other writers, she uses theoretical and speculative words and metaphors, but her writing is consistent in their usage and gives a feeling of being tightly knit. And that doesn’t mean that her writing is more difficult to understand compared to others. It is true that you have to be focused until the very end, but her writing is relatively easy to understand. (I am very critical of how theater critics write. I want to ask them what they do to make it so difficult to understand what they are writing. I am sure that stage directors aren’t able to understand critics either!)

Another characteristic is that she places the emphasis at the very end of her pieces. Most writers do this, but she does it persistently and succeeds occasionally. For instance:

“For our taste, which is used to overeating and strong spices, it was a little too bland.” (On Klaus Metzger’s direction of The Visit performed by the National Theater Company of Korea, in Auditorium, December 1994.)

“If you have somewhere to be, you must leave the warmth of a room and head into the cold winter storm. Go—as your desire leads you, to the path the play wants to take you.” (On Kang Hwa-jeong and Mythos’ Invitation to the Museum that will Disappear, in The Korean Theater Review, February 2001.)

“The scene where a girl from Yeonbyeon was at a loss because of love, or the scene where two men were talking and sharing drinks, were both so calm and clear that I nearly felt sorry about life.” (On Park Geun-hyeong’s Sunday Seoul, in Auditorium, August 2004).

In her final sentences, I feel as though she takes a step back from the subjective view with which she wrote the rest of the piece, and looks at everything objectively. Regarding this point, Kim said, “Critics sit in the audience seats to study and analyze performances, but they also need to look at the play as a whole. You have to see the whole play.” That was the intention behind her writing, she said. So it seems I wasn’t too far off the mark.

Another thing. She takes the titles and twists them for use in her writing. She said, “The title contains the essence of the play, so using that can attract more attention.”

“The pathos (gam) that we feel is no longer sympathy (gyogam) but turns into regret (yugam).” (On crossover performance When Pathos Enters Our Heart, in Auditorium, August 1998).

“Therefore we would need to wait longer for the distance (geori) between the performance and the audience to narrow beautifully.” (On Beautiful Street (Geori) written by Lee Man-hee and Kang Yang-geol, in News Plus Vol. 61, November 28, 1996).

“Therefore the love story of the ‘woman, young and special to him’ is unfortunately neither fresh nor special.” (On His Young and Special Woman by Theater Company Bongwonpaem, in News Plus Vol. 34, June 16, 1996).

There are several grandiloquent words she likes: gojol (quaint; simple and honest beauty without artifice), wiban (perfidy), dojeo (erudite), and hyeonhyeon (manifestation). I’m not sure where she learned them. She also often uses the following words with special meanings: jijeom (point), danja (monad), jillyo (substance), bideungjeom (boiling point), gilhang-hada (contentious), seoseong-inda (hover), muhwa-sikida (obliterate; this word isn’t even in the dictionary), and sohwan-haenaeda (summon).

But these characteristics are only a part of her writing. Perhaps there’s a more encompassing way of framing her writing? (It’s beyond my pay grade.) Fortunately, critic Kim Yun-cheol saved me the trouble. In 2006, he had this to say in a review of Kim Myung-Wha’s three books: “Kim’s writing is fun to read as she naturally reconciles conflicting concepts and characteristics, such as delicateness and persistence, sentience and reason, literature and analysis, masculinity and femininity, firmness and softness, logic and creativity, expertise and popular appeal.”

Quite the compliment. Regarding this analysis, Kim said, “I’m not sure. I think that there is an orientation in my writing. Everything has something sacred and something secular. That’s the way of the world. And a play is a compressed version of life.” She meant that using conflicting or opposing concepts is only natural.

Unrelated to analyzing her writing, I really enjoy some of her expressions: “Democracy that hungrily devours idealism and wipes its lips with the handkerchief of apostasy” (‘Seoul Ensemble “Fashion”’ in News Plus Vol. 30, April 18, 1996); “The fate of an actor whose life has been mortgaged to create a fictitious moment called a musical” (On the musical 42nd Street, in News Plus Vol. 38, June 13, 1996). (News Plus was a weekly magazine created by Dong-A Ilbo. I was proud to learn that News Plus had long dedicated some pages to play criticism. The magazine has now changed its name to Weekly DongA Magazine.

One thing you’ll immediately notice in her writing is that in 80 percent of her pieces she starts off with the positives and switches to the negatives with a “however” or “nevertheless” in the second half. She may need to think about how to change this stereotypical structure.

Let’s now ask about what she critiques rather than her critiques themselves.

What kind of works do you watch most often?

“I go for the ones that would spur discussion—more meaningful plays than commercial ones. When I was younger, I was frustrated with Korean theater. I thought that plays by younger writers would be the ones to break through such situations, so I watched a lot of them. And I still do.”

Do you take notes while watching plays?

“I did, initially. But that can bother people in the adjacent seats and cut off an actor’s flow. So now I only take mental notes and just watch the performance.”

You don’t mention acting as much in your writing.

“People say that what makes plays is acting, but it’s not easy to capture the acting in words. I do try to write about it, but I end up talking about the actors rather than their acting, just saying whether they do well or not. I think other critics think about the same thing, or they just write without thinking about it. It’s something I’ll have to work on all my life.”

And isn’t it possible for your criticism to be wrong? For instance, you were critical of Nanta when it first came out but has grown into a great cultural product 20 years on.

“The Nanta performances we have now are a huge upgrade over the initial performances. The producer’s belief that it would work with the public, his support, and his will probably helped improve the show. And the success of Stomp and Tap Dogs, which were similar shows, probably had an influence as well.”

Critiquing Ariel Dorfman’s The Other Side, you said that the structure and the significance of this work is similar to that of Waiting for Godot. I’ve seen the latter, so this kind of analysis is useful for me. Where do you get these ideas?

“I’m not a genius. I sit and write and rewrite and revise and eventually arrive at something like that.”

Any conflicts with people who disagree with your pieces?

“Some people call at night to complain, others ignore me. You have to be prepared for things like that to be a critic. Of course, no one is forcing you to write if you don’t like things like that. But if you’re looking to make a moderate income and maintain a moderate relationship with others, why would you be in criticism? What’s the value of critiquing? I go through these questions and eventually arrive at the conclusion that I need to write properly. I do try to stay away from becoming emotional in my writing. I’ve received criticism of my own work as well, and you know when someone is writing emotionally. When I write, I try to avoid that mistake.”

But there are various problems in theater criticism.

In 2002, seven critics including Kim Myung-Wha, playwrights, directors, and actors held a meeting under the theme of ‘Korean Theater Criticism Today’ (January 2002, Korean Theatre Journal Reissue No. 4), to discuss the problems of theater criticism.

Some of the issues that were raised included:

– lack of readers

– monotonous writing style

– too much focus on the plays themselves and no mention about directing, actors, or sets,

– too many critics who aren’t in theater,

– indifference to the connection of plays to society,

– lack of harsh criticism due to ‘theater familism’

– emotional struggle without counterarguments and debates

– and the lack of periodicals for publication.

At this meeting, Kim Myung-Wha said, “The main function of criticism is not in judging but in reading accurately; not simply looking at the surface but combing through the details.” In this interview, she said, “It’s good to watch plays, but it’s also necessary to read the thought that went into writing a given play and the changes as well. Everyone is trying to do everything themselves rather than watching others develop. Again, this is big problem in the theater community.

Perhaps that was the reason she was concerned about this:

“What kind of pieces do I need to write for people who have no connection whatsoever to plays. The general reader hasn’t seen a single play in his life. What do I need to focus on? Rather than an impartial criticism, isn’t my role to tell them about the rapture of watching plays?But do I still find them rapturous myself? If plays are concentrated visions of life, shouldn’t the focus of criticism be on reaching life through plays?” (The Curtain Goes Up At 7:30 pm, Theater and Man Press, 2006).

And her efforts are ongoing.

As I read her writing and articles on the meetings and discussion sessions that she participated in, I came to land on a fundamental problem. Ultimately, plays are for the audience, and the audience determines whether a play is a success or a failure. And criticisms become meaningful when the audience reads them. However, her writing is devoid of the audience’s perspective, assertions, or demands. Completely.

Regarding this point, Kim said,

“I watch performances with a group of the audience and I react. The audience’s reaction comes over me in waves. So I believe that my writing speaks for the audience.”

She means that critics speak for the audience. And she’s not alone. Most critics probably they have. I’m not sure if that was true in the past, but it is certainly not true anymore. I believe that it is wrong for writing that discusses theater to not include a single piece of information about audience reactions. I asked her to share this with other critics when writing. I believe it is at least worth discussing.

Redolence (Chimhyang), released in 2008, received the first Cha Beom-seok Play Award. Kim said she took out her work three weeks before the deadline and polished it. It depicts the conflicts and reconciliation of a man with his life, after partaking in left-wing politics and defecting to North Korea and returning to his hometown after 56 years. In the play, someone says that a tree that has been planted for 1000 years gives off a fragrance (redolence) and takes away all the difficulties of the world. But this play shows the audience that human affairs are also dependent on people’s will | Cha Beom-seok Theater Foundation

2. Another path, playwright

Kim debuted as a playwright after receiving the Samsung Literary Awards for Plays in 1997. Therefore it has been 20 years since she debuted.

She’d previously submitted five or six of her scripts to the Spring Literary Contests, which are hosted by Korean newspapers, but to no avail. She was extremely on edge at the time. Her (eventual debut) play, Birds Do Not Cross the Crosswalk, failed to make the cut, as did the plays that would later solidify her position as a playwright—First Birthday (Dolnal), Oedipus, That is Human, and Cello and Ketchup. (Just goes to show, you never know what life will bring!)

When asked about her works that were meaningful to her, she chose Birds… (1997), First Birthday (2001), and Redolence (2008).

Birds… helped me make a grand debut. When that happens, some people fall into a slump. First Birthday broke that jinx and brought me more renown than I deserve. And Redolence is significant in that it received the first Cha Beom-seok Award.

First Birthday was praised for hyper-realistically depicting the way in which the 386 Generation’s beautiful dreams and ideals faded into a shabby reality, and there have been detailed and analytical critiques.

One review also focused on the fact that Kim was a woman playwright.

“Young woman playwright Kim Myung-Wha depicts a scene of young women drinking together and attempts to find the key moments in their lives. In presenting the scene, she reproduces the ripples of emotions that men are unable to portray in subtle and realistic ways.” (Kim Bang-ok, ‘First Birthday food, drinks, madness, and women and men’, in Theater Criticism, 2002).

But Kim also said that the play received a lot of criticism.

“People told me not to play with food. The first two acts are normal, everyday scenes, but the third act turns into chaos that glimpses into people’s minds with hints of homosexuality, so they said it wasn’t realistic. Some even said it wasn’t a good play at all. When I first published the play, realism wasn’t received favorably, and the play was dark too.”

I read the play (I didn’t get to see it performed) and asked her two questions.

Isn’t Hwang Jeong-suk too obedient? Women aren’t like that these days.

“Even the most progressive person can be conservative inside. Some of my friends are like that. They live dual lives. Jeong-suk and Gyeong-ju could be the same person. The only difference between the two characters is that Jeong-suk gave up her dreams and Gyeong followed them. I’m not very optimistic about life.”

Are all the people of the 386 Generation who aren’t successful and simply lead ordinary lives pitiful?

“Most of the characters in the play are people who don’t have stable positions in society. Some are hesitating over being corrupted by the contradictions around them… Compared to their innocent and brilliant youth, yes, they are pitiful.

Kim has affection for all her plays.

“I wanted other plays to succeed, but they didn’t. So I feel for them. Some were loved by the people, others weren’t. But the world isn’t always right.”

Her ‘greed’ was also awarded with prizes.

She won the Kim Sang-yeol Theater Award in 2000; the Dong-A Theater Award (play) and the Daesan Literary Award (play) in 2002; the Grand Prize in the Asahi Shimbun Theatrical Arts Awards in 2003; the Today’s Young Artist Award from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2004; and the 10th Yeo Seok-gi Theater Critic Award and the first Cha Beom-seok Theater Award in 2007.

There is something I must mention about Kim as a playwright. That’s her relationship with directing.

In the author’s note at the very end of her play collection Cafe Shinpa, she harshly criticized the performances of two of her works (Oedipus, That is Human and Cello and Ketchup), which she explained were experimental works, for having been interpreted completely differently from her original intentions.

She railed against the performances, saying that “The premiere performances of original plays should convey the author’s intent as much as possible. If a director sees a play as so flawed that they end up changing parts against the author’s wishes, then they shouldn’t have chosen the play in the first place. Playwrights don’t write for the preferences of directors. ”

This was an opinion she had for a long time. In the review of Feeling, Like Paradise (Seoul Arts Center), written by Lee Gang-baek and directed by Lee Yun-taek, which premiered in 1998, Kim harshly criticized the director for thoroughly ignoring the writer’s intentions. “The only thing that’s left is the director’s desire that has obliterated the writer, and an obsession with secular forms rather than the feeling of a paradise.”

It has been over 15 years since the premieres of these two plays. So I asked her if she was still angry about the direction. And the answer she gave me was unexpected.

“I read Cello and Ketchup again before the publication of the collection. I thought, ‘The director must have had a real hard time,’ and that I was too young. It would have been difficult for an ordinary reader to breathe (to keep up with the play). I said I wasn’t optimistic about life, and I also thought that I wrote Oedipus, That is Human without really understanding what life was.”

Do you often read reviews of your work?

“After I made my debut, I did read a lot about my work. There were good reviews, but some were emotional and others were violent. I felt that the latter types of reviews didn’t properly evaluate my work. So I started reading less and less.”

The worst chronic problem for play criticism is that not many people read it. Yet even a famous theater critic doesn’t read other critics? To that, she answered, “But I often do.”

Let’s now hear about Kim Myung-Wha’s opinion on her position as a playwright and theater critic. She said similar things in various places.

“Since I am both a playwright and a critic, I don’t agree with idolizing or isolating each field. I always believe that what is important is the development and improvement of plays themselves. Isn’t it enough for my creative efforts to open eyes for criticism and my critiquing efforts to impact creations, and ultimately all my efforts to contribute even a small amount to enriching the Korean theater?” (In celebration of Eric Bentley winning the Thalia Prize, The Korean Theater Journal Reissue No. 23, 2006).

She wants to focus on creating a synergy effect and disregard the criticism she faces for working as both a playwright and critic.

Kim was in charge of adapting and directing the musical play Solangsiul-gil, staged at the Daejeon Arts Center in October 2016. But instead of using her real name, she used her childhood name, Kim Nan-hee. The play is set in an alley in Soje-dong, near Daejeon Station, where about 40 official residences for railroad workers built during the Japanese colonial era still remain. Solangsiul-gil means a sparkling path to Solang Mountain. Four friends who grew up in this area and left town after graduating from school come back for their reunion. The picture is a scene of the four friends asking about their friends to the old ladies living in town | Daejeon Arts Center

3. A new challenge, directing

Kim Myung-Wha says she understands the directors who interpret her work differently but seems reluctant to let the issue go.

On June 21, 2017, she registered a one-person theater company called Nanhee Theater Company at the National Tax Service (Nanhee is Kim’s childhood name). She wants to direct. Why?

“I can create the images and the world that I want. In the past, theater centered around writers and focused on text. But as directors gained power, writers were selected by directors, passively. And directors gained even more control with national and other publicly funded theater companies adopting producer systems. (What are you going to do about staff?) When you have staff, then the priority shifts to taking responsibility for them, so I’m not planning on taking any. I’m thinking about getting people together to stage shows when necessary. Within this year, I want to restage Solangsiul-gil. And Women’s Stories was previously a combination of amateurs and professionals, but I’d like to do it with professionals.”

Solangsiul-gil was a musical play performed at the Daejeon Art Center in October 2016, adapted and directed by Kim. Women’s Stories was performed by the Ewha University Alumna Theater Company in 2010, and was also written and directed by Kim.

There’s another reason that she wants to direct.

“I want to put my ‘sad plays’, ones that weren’t performed or haven’t received proper attention, on stage if possible.”

Did you have some kind of an emotional epiphany?

“Now that I’ve entered my 50s, I realized that I only have about 15 years to work with a clear and lucid mind. So I thought that I should do what I really want to do, even if I have to pay for it with my own money. (It seems like you’re trying to go down a difficult path.) I’m manmandi (slowly in Chinese). I get anxious about little things but I’m cool and composed about big things. So I see need to worry about it.”

Kim once wrote, “It seems like the theater won’t be satisfied with me and constantly demand, ‘Bring more! More!’” Is directing along the same lines?

“When I was young, I loved working, even to the point of exhaustion. But now I sometimes get tired. I have to manage my energy. Nevertheless, the theater will continue to ask me to bring more.”

Now you’re a well established playwright and critic. Are you aware of that when you write?

“No. I’m not very good at doing things out of habit or tradition. I have an inferiority complex with things like that. I’m not very good at making friends, and I tend to come off as a bit standoffish. I’m not good at staking my claim on something and keeping it. I’m not good at things like that. I’m always hovering along the boundaries. So it’s great that I’m a playwright.”

4. Daily life and misconceptions

I asked her about what she’s doing now.

“I’m rewriting Oedipus, That is Human to publish a collection of works, and I’m interested in mythology. Myths make you think about the big picture beyond the little things. When writing Dream, I read about Korean mythology in The Romance of Three Kingdoms, and when writing The Sound of the Moon, I encountered gayageum (a traditional Korean string instrument) in the History of the Three Kingdoms. Writing plays involve a lot of calculations. But you can make jumps and leaps in myths. It’s a bigger scale. I like having these two things mix.”

The world of mythology seems like a mountain that playwrights have to overcome as well as a sacred ground and a safe haven, considering that a large number of playwrights are wrestling with mythology both in and outside of Korea.

Kim is planning on publishing a collection of plays, including The Sound of the Moon, The Desire of the Wind, The End of the Palace Restaurant, Pot, and Hamlet: a Meditation on Death. She is also going to publish another selection by revising the plays in Cafe Shinpa: Birds…, Oedipus, That is Human, Cello and Ketchup, and Cafe Shinpa. First Birthday and Redolence have already been published separately.

What’s the point of revising the works that have already been performed? And is it right to revise them?

“They’re not performance scripts but plays, so you can revise them. Shakespeare has several versions of the same plays as well. I want to bring my plays closer to perfection.”

Sometimes I ask people in theater if they make enough money. Most tend to avoid direct answers, but they are all dedicated. Kim said she is writing, researching, and also taping playwright Yun Jo-byeong’s story—Kim is writing an ‘oral history’.

“I received the proposal to do so in May and started in August. Playwrights rarely meet other playwrights. I’m learning a lot.” Perhaps in 20 or so years, a younger playwright will come meet her and record her story. (That would be a huge honor.)

I’d like to introduce one misunderstanding I had about her that was corrected during the interview. I thought that she was involved in the democratization movement as a college student.

That wasn’t only because Birds is a story about a college theater club and the characters of First Birthday are the 386 Generation. She doesn’t hide her political leanings in her work.

“Because here and now this is the country where sex torture and chaotic hearings are buried under the Olympics, the last divided country on Earth where the flames of lust still burn strongly in the motels by the Bukhan riverside on weekends and go wild for the upcoming 2002 World Cup on weekdays, our beautiful Republic of Korea” (‘The Curtain Goes Up At 7:30 pm’, in News Plus Vol. 49, August 29, 1996).

“I heard the shocking news about the death of a former president while I was writing. Is this really the end of the weak liberals? The ideals of progress couldn’t even do anything when faced with the tsunami of neoliberalism across the world, and the weak efforts that existed were completely rejected in their struggle against the conservatives. Will our history be recorded as a complete failure? (‘The Narrative of Realistic Criticism Returns’, inThe Korean Theater Journal Reissue 33, 2009).

But unexpectedly, she said,

“I wasn’t involved in the democratization movement. The most progressive clubs in schools were theater clubs and talchum (traditional mask dance) clubs. Among the members, I was the only one for doing art for art’s sake. So I still feel terribly guilty about not having participated much in the rallies. In 1987, when I was a senior in college, I went to several rallies, but I stopped. I’m only writing what they can’t.”

5. Several questions and family

In the forewords to her collection of reviews and critiques, Kim Myung-Wha confessed,

“I tried to go on stage because I wanted to be an actor, but I gave up because of stage fright. I also tried at being an assistant director but couldn’t adapt to the militaristic life. I tried studying, but the curriculum was too West-centered, so I had no means of figuring out my theatrical identity. And I tried my hand at directing, but because of my over ambitiousness, I made the lives of people who work with me miserable.”

So why didn’t you leave the theater world?

“I didn’t particularly like other things. I was captivated by theater.”

She went on to say, “As I grew older, it became possible to accept my surroundings.” I asked her “Can I write that you changed?” and she answered, “Yes.” She said she had a hot temper when she was younger, but not anymore.

Another thing. I asked her why she studied educational psychology instead of theater if she loved the theater so much.

“I applied to the majors I could with my grades.”

I once again confirmed the deep-rooted evils of the Korean education system.

Unable to find interest in educational psychology, Kim asked to join the theater club at the teachers’ college in the second semester of her first year. She said the theater club was the only club accepting new members at the time, but something must have tugged at her. (She said in third grade, there was an assignment to choreograph dance moves to songs. Other kids in the class didn’t take the assignment seriously, but she and a couple of her friends choreographed dances to two songs. This was her way of saying she had a talent for performance.)

For about four months after graduating from college, she worked as a TV show scripter, but even the ample wage couldn’t break her dream. She received her Master’s and PhD at Chung-Ang University and taught at Chung-Ang University, Korea National University of Arts, Seoul National University of Science and Technology, Graduate School at Seoul National University, Korea University, and Seoul Institute of the Arts.

Have the theater people treated you differently because you didn’t start out in theater?

“I don’t tend to stick to groups, and I’m not mainstream. I have a habit of staring, so I got scolded once. That makes people uncomfortable.”

Kim enjoys being alone. And she is also a night owl.

“Writers tend to like being alone. But at least I’m not a poet or a novelist. I’m thankful that I get to work with people. Plays offset my fate of loneliness. Sometimes, I get tired because I have to be around people too much.”

She uses a dialect, which makes it clear that she is from North Gyeongsang Province.

She was born the youngest in a family of six girls and one boy in Gimcheon. Her parents had five girls and one boy, and decided to try again for another boy and got Kim Myung-Wha. Her father, who ran a briquette factory, apparently went out that day out of disappointment.

But Kim has fond memories of her father. In Cafe Shinpa, there is an old man who says that he likes modern plays. He was modeled off of her father. She describes the line as funny but also painful.

He father passed away in 2014. Recently, Kim watched the performance of Spring Day, whose main character is an old father. She said the play felt different than when she’d seen it before. “What do you mean?” I asked, and she said, “When my father was alive, it felt as though the conflict between the old father and the young sons felt stronger.” It sounds like she’s saying that her feel for conflict is weaker now that her father has passed away. The absence of a family member affects the lives of the living.

Nevertheless, I couldn’t tell that she was the youngest. I only noticed her reticence and cynicism. She laughed and said, “I act like the youngest with people I’m close to. But it’s probably because I’m now so used to being the thinking writer and the thinking critic.”

I made the same request I ask of all my interviewees: Do you have anything to say to Korean theater?

“We need to stop throwing out plays after one performance, to read the text more closely, to develop a reasonable standard for guarantees, to create an efficient joint work system, and to make the funding system more transparent.”

She is a playwright and critic who hasn’t yet reached her ‘boiling point’. She still relies on ‘monadic’ life. She pursues the ‘manifestation’ of plays and critiques that ‘break’ the ordinary world with the ‘materials’ derived from her experience and conviction, but has a charm that is remarkably ‘honest yet simple’. She also ‘hovers’ around the boundaries beyond writing/critiquing and directing, and ‘summons’ the reasons why conflicting values compete, all the while sure of the fact that there is a way to ‘obliterate’ the worries of the world. (I tried to describe her using the words she uses often.)

I’d like to tell her something that I recently heard from a retired general: “A soldier should not fight with plans but with the enemy.” This means that if you ignore the field and reality and only stick to the plans made before the war, you’ll lose the war.”

I think theater is the same. Reality changes faster than enemies. What is the significance of plays that aren’t written from experience and critiques built on literary theories? I hope that Kim Myung-Wha becomes someone who lends an ear to such questions.

Have a question for the writer? Send us a mail or sign up for the newsletter.