Ruin porn is still haunting Seoul and will be for a while longer. Ask hipsters who like to insta-hunt cool cafes in places like Seongsu.

Cos the city has seen one too many glowing, shining skyscrapers armored in mirrors. Cos we feel the rapid development enjoyed by our 386’ers has no more glitter to leave us.

There’s no way artists will miss this chance. They scour Seoul to dig up fresh new ruins. And they put their own works up in them.

Like the PR man who places his client’s luxury product next to some renaissance artwork, like the tribesman who eats his opponent’s brain from the skull he just cracked open, they attempt to drain ruins of their aura.

One interesting place, however, was brought to my attention.

The name of the place is ironic in itself. Gangnam Apartments, in betrayal of their own name, are located in Gwanak-gu. While the name is literally correct—the building is located south of the Hangang river (that’s what gangnam means)—their value as properties and as a neighborhood is far from being Gangnam-gu.

The apartment complex is 44 years old and was designated a disaster-prone facility in 2001. Pretty much the entire complex has been abandoned ever since.

A group of artists somehow managed to stage an exhibition in cooperation with the reconstruction association.

The ruin of one apartment building became a canvas and exhibition room.

What makes ruin porn porn is that we often objectify the ruin, stripping the human residue off and even stepping on it.

I enjoyed the beautiful ruinous scenery until at the top of the building I spotted drying laundry on the balcony of another building, across from where I stood.

There are still people living in these apartments, it means.

Later, on my way out after roaming the streets I saw several people in shabby clothes coming out of one of the buildings with household items in hand. They were speaking in Chinese. One artist told me it seemed there were Chinese migrant workers squatting in some of the apartments. Every time the artists break open one room to be used as an exhibition storage room, the squatters seal it up the next day.

With the local authorities designating the place as dangerous, the complex has clearly become a slum.

It’s hard to believe the buildings are still standing nearly two decades after the warning. Reports say that owners of the complex pursued reconstruction multiple times but kept failing.

I kind of understood why. The neighborhood didn’t use to have much going for it. Surrounded by the Guro, Gwanak, and Geumcheon districts, the land probably wasn’t that attractive to developers until recently. Also, the neighborhood was until recently brimming with factories. The original name of the nearest station was Guro Industrial Complex.

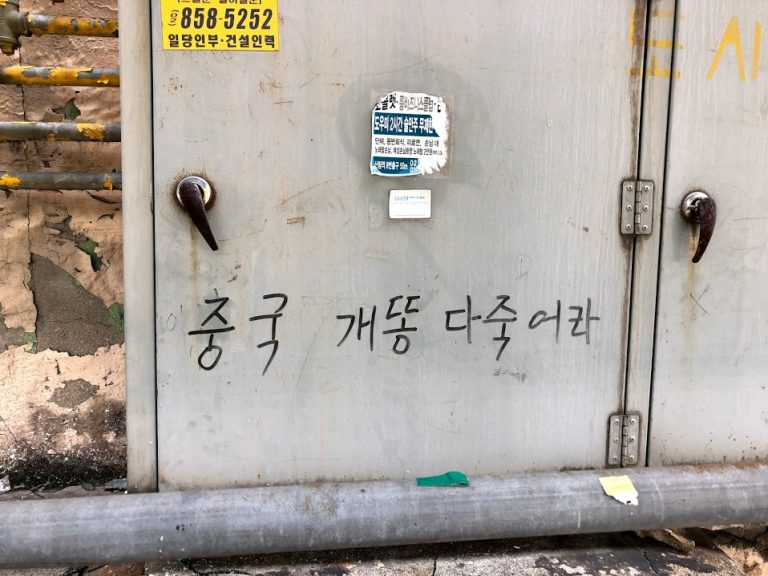

Then was when I at last realized why there were hate scribbles on the walls. This one reads, “Die, all of you Chinese pieces of dog crap”.

Many Chinese workers still dwell in these apartments. The place is close to Daerim, which has long been Seoul’s miniature China town. And then there’s the cheap rent.

Anyway, this won’t last long. The apartments are to be demolished and replaced by a new, tall and shiny complex. The powers that be finally decided to do something about the slum and a reconstruction project led by the government housing corporation was approved last year.

Illustration of the reconstructed Gangnam Apt by Seoul Metropolitan Government

Apartment towers as high as 35 stories will replace these ruins. That there is not much time left builds more thirst for the canvas itself than for the artwork.

One particular piece of art, however, managed to grab my attention.

The artist Kim Lee Park[1] decorated the ceiling with ribbons that are usually attached to wreaths in South Korean culture.

Wreaths flow though the veins of Korean social life: you get them when you marry and also when your family members die.

Turn on any news network channel and you’ll see adverts for wreaths, competing for the cheapest price.

While it is called a wreath, it’s more like a model of a tropical tree ornamented with flowers.

I said model because it is an artificial tree made of plastic and when you see one you may wonder why and how a certain tropical plant became the archetype conveyor of welcome and congratulatory messages in a land where tropical plants cannot grow. Jo Hye-jin did a series of interesting research-cum-artwork on Korean wreaths.

The ribbons bring a message and show who the sender is. When you pay a visit to a wedding ceremony, one of the first things you do is see who sent the wreaths. They show who the hero/heroine of the day is and who his/her parents are. The ones that came from famous politicians and owners of big corporations are displayed in front.

The artist put a wicked twist on this, writing celebratory welcome messages on the ceiling of a 44-year-old house, the demise of which will happen within a few months.

“Thank you for moving in”

But I also discovered another kind of message in these ribbons:

“Although we are not an ordinary family, it may also be the case that we’re more experienced than others so let’s be well and happy!”

Kim told me some messages he wrote on the ribbons were from the postcards and letters he found in the rooms and vicinity.

“I hope dad is living well. (It’s) become harder than before but now only happier days are ahead.”

It looks like a divorcee and her children came to live here. And they did try to hold on as we can see from the messages. What happened to them later we do not know. We only know that this place is going to blow up soon.

Kim also found interesting things from the garbage and displayed them in the room.

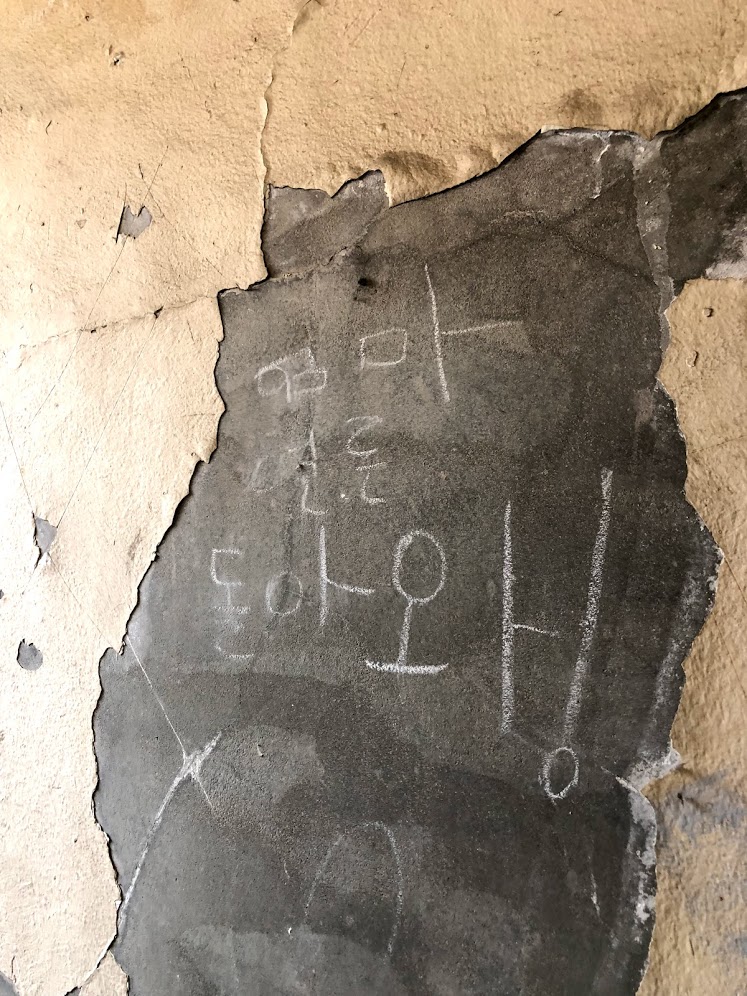

Someone obviously practiced his Korean writing here.

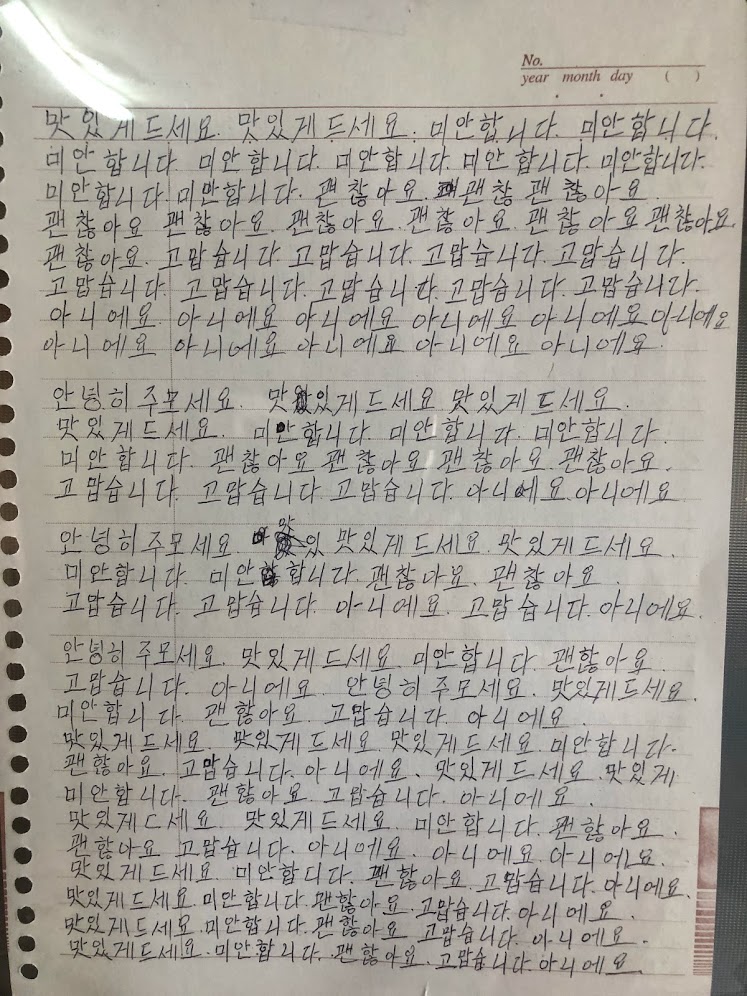

“Enjoy your meal. Enjoy your meal. Enjoy your meal. I am sorry. I am sorry. I am sorry. I am sorry. I am sorry. I am sorry. It’s okay. It’s okay. It’s okay. It’s okay. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. You’re welcome. You’re welcome. You’re welcome.”

This seems to be part of a Korean textbook for Chinese speaking people.

What grabs you about this seemingly ordinary piece of a Korean learner’s book are the scribbles at the edge of the page:

“There’s no one to believe in this world.”

“All talk no action.”

“I’m free until next week.

God only knows what led this person to write these kinds of lines.

All this brings the people who actually lived in this place closer. They ceased to be just some faceless entities. Suddenly they have faces and stories, glimpses of which we are able to catch. I might never be able to meet them in person but at least I left the building with more respect for the people who once called it home.

“Mom, come back soon!”