A scene from the film Modern Boy, set in Gyeongseong in colonial Korea | KnJ Entertainment

There’s a word that I come across on the streets very often these days: “Gyeongseong”. A word used across East Asia to refer to capital cities, gyeongseong appears now and then in the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty and other documents from the time. However, the word has the power to bring to mind the image of colonial Korea probably because, on September 30, 1910, after Japan’s annexation of Korea, the Japanese Government-General of Korea issued an edict that renamed Hanseong (the name for Seoul during the Joseon dynasty) to Gyeongseong.

Despite this inherent disadvantage, Gyeongseong brings up more than negative perceptions. Western culture that was changed in Japan reached Korea, changed the city, and affected lifestyles. In this process, “modern boys” and “modern girls” who were open to new cultures and who dressed up neatly in the clothes we now see in black and white Hollywood movies became fashionistas of the time, and Gyeongseong emerged as a trendsetter, physically, and as a refuge for modern boys and girls, psychologically.

It is not hard to find attractive and charming aspects of modern Korea’s urban culture in the representations of Gyeongseong in recent television dramas and films. Perspectives on Gyeongseong in colonial Korea are currently diversifying. Some may even call it unproductive to view Gyeongseong as either negative or positive. However, in the deluge of the word Gyeongseong in our lives it is rather concerning that we are encountering situations that bring to mind the prejudiced term waesaek (meaning Japanese style).

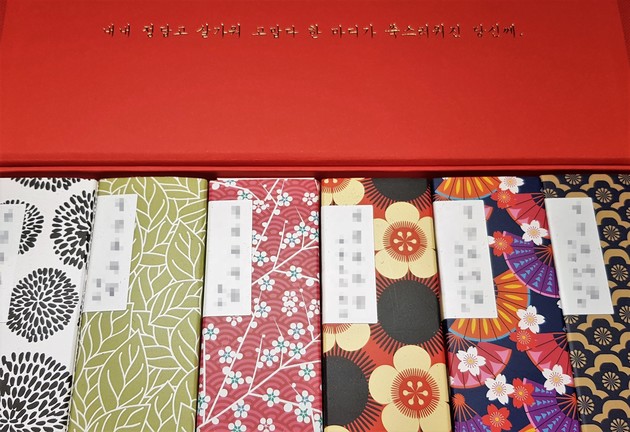

A few days ago, I was shocked when I stopped by a store with Gyeongseong in its name that sells pound cake. Located in Ikseon-dong, which has recently become a hot place, the store was decorated in an antique style, and had the vibe of a place that would become popular on Instagram. Among the products on display in the store, the one that caught my eye was a cake set. Six different types of pound cake was wrapped in beautiful paper sheets and placed perfectly in a box. The set looked like it would make a great gift. Until, that is, I realized something about the patterns on the beautiful paper.

A cake set package from the store | Harry Jun

As I grasped the truth about the colorful wrapping paper, my head went cold and blood rushed to my heart. The sheets of vividly colorful patterns of flowers and fans and geometric shapes were wrappers for certain products—the wrapping paper used for the souvenirs you see in Japan. And we’re not talking the type of handmade paper you find in Kyoto, the quintessence of Japanese culture. This was the kind that is easy enough to find online with a few clicks.

Some might ask: How can you be sure that these designs are Japanese? I saved digital images of the wrapping papers and started searching for them online. After an hour, I’d found most of them on stock image sites. And the one keyword that appeared repeatedly was “Japanese”.

I’d like to say one thing, so that there is no misunderstanding. I am not criticizing the fact that the wrapping paper at the store mentioned above was not handmade or professionally designed. My problem is not the quality but the kind of patterns and images. All of the images were easily found with the keyword “Japanese”. In other words, these wrapping papers are not just “Japanese style” but appropriations of the Japanese identity.

Some might tilt their heads and think: Look how many Japanese restaurants there are around the world, and how Korean people visit izakayas at night. We have not outlawed the Japanese languages and are certainly not censoring Japanese things. So why are you still talking about the time-old waesaek? Those people would be right. Thanks to the open-door policy on Japanese popular culture, enacted in 1998, the Japanese culture is now legally loved by Koreans. People may like or dislike the Japanese culture for psychological reasons, but countless Japanese products are circulating in Korea. You can go right now to any nearby convenience store, and you won’t find a single one that does not sell snacks, drinks, and beers imported from Japan.

The problem is the context and situation. It is plain as day that the Gyeongseong in the store’s name refers to Seoul during a particular period in time, specifically the 35 years from September 30, 1910, to August 15, 1945. No one would object to the fact that the store has made the unique atmosphere of the time its identity. But why are the pretty wrappers for the pound cakes covered with visual elements rooted in the Japanese culture? Isn’t the image of Gyeongseong that we have a new world full of new things, where modern boys and modern girls walked around? Since when did our image of the cool Gyeongseong began to be equated with waesaek, the result of Japanese aesthetics?

And when you think about the place pound cakes originated, you have to go all the way to England. From the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, the design trends prevalent in England and across Europe were art nouveau and art deco. At the time, Gyeongseong was fast absorbing global trends. On wrappers at a cake shop in Gyeongseong frequented by modern boys and girls, which would have seemed better: art nouveau and art deco designs or traditional Japanese designs? I think the answer is clear.

An example of modern wrapping paper with art nouveau designs | Norman’s Printery

It is a historical truth that Seoul was called Gyeongseong while Korea was under Japanese rule. The largest city in Joseon, Gyeongsong attracted groups of Japanese tourists in search of a different kind of culture. The city was gradually modernizing and represented the amalgamation of the legacy of Joseon and a new culture. Physically it was a Japanese colony but culturally it was anything but. Would it be an exaggeration to say that the designs of the wrapping paper at a small pound cake shop in twenty-first century Seoul touch upon the wrath Koreans have regarding Japanese colonial rule?

Next year is 2019, only a year from 2020, long considered the paragon of the future and also the 100th anniversary of the March First Movement in colonial Korea during which countless Korean people came together in nonviolent protest. At such a historical moment, if a perspective that equates Gyeongseong and Japan were to casually seep through our minds, would it not feel as though the years that we have spent physically and mentally trying to overcome Japan have been in vain? It’s okay if you think that I’m overreacting or deluded. But before a small spark begins to grow and burn down a forest, perhaps we need to think, reflect on ourselves, communicate, and discuss.