The third in an award-winning series of interviews with Korean theater professionals, first published in The Dong-A Ilbo.

Listening to her speak, I realized that that some people’s lives really do ‘change in a flash’. “I enrolled in Yonsei University with a major in Atmospheric Sciences in 1995. But I realized I wasn’t really interested in my major. So I studied for the college entrance exam and entered Yonsei University again in 1997, this time with a major in Computer Science in the School of Mechanical Engineering. After three years in school, I took a year off for personal reasons. During that time, I came across a TV program from Japan’s NHK, which aired performances of the Takarazuka Revue, once every week, around noon. And I fell in love with it. I think I was fascinated by the elaborate stage, costumes, and songs. I became a huge fan of Asato Shizuki, in particular. I didn’t know that all the members were women when I first started watching, so I wondered whether the cross-dressed women were men or women. Then I searched the theater troupe on Yahoo and found out what kind of performances they do. I studied Japanese, frequented their fan site created by their Korean fans, and ended up becoming an administrator of the site as well. I’d become a Takarazuka otaku—obsessed with the Takarazuka Revue. When I heard that Asato Shizuki was leaving the troupe, I went to Japan for three days to see her last performance. I only remember crying during the whole performance, watching the person I adored for a long time in real life. When I came back to school, large tiered lecture halls seemed like theater spaces to me, and professors and students seemed like actors. I couldn’t get it out of my imagination. So I studied for the college entrance exam once again, and enrolled in Hanyang University in 2001, as a stage directing major in the Department of Theater and Film. I was 26.”

She chose a major in stage directing because her performance test scores were too low for her to dare dream of majoring in acting.

When I asked, “Do you ever regret changing your career?” she answered, “Never.” Who is she? She is Choi Boyun (42), who once again changed her career from directing to lighting design. I met her at the Dong-A Ilbo on March 30.

I still had a nagging question about her so “easily” changing careers. And also about her decision to abandon the prestige of being an alumna of the School of Mechanical Engineering at Yonsei University and choose an uncertain future.

“My family ran cram schools for abacus math, arithmetic, computer, piano, etc. I started learning computer in fourth grade, so I was able to hang in there at the School of Mechanical Engineering. And there weren’t many women in the school. I’d been thinking that I should just get a decent job after graduation or get married. So I knew that this was the only chance I had to change my life.”

To sum it up in a line that you might come across in a play, she “knew she’d lose the reason for her existence if she didn’t pull herself out of a rut, and in order to overcome that fear, she decided to accept her uncertain future.”

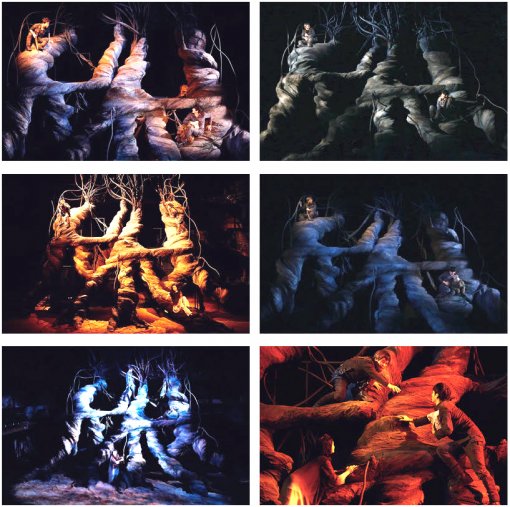

Soldiers in the Tree (a play by Ryuta Horai), performed in Jayu Theater at the Seoul Arts Center from December 2015 to February 2016. The play tells the story of two soldiers who lived atop a tree for two years to avoid enemy troops. The gigantic banyan tree was the fourth actor in the play. Lighting designer Choi Bo-yun indicated the two soldiers’ emotions, the flow of time, and the changes in the environment through the lighting that fell on the tree | Choi Boyun

Let’s ask her why she became a lighting designer instead of a stage director.

“Stage directing means you have to experience all kinds of things necessary to put on a play. I first took charge of lighting in my third year. It was for a play in the Daloreum Theater at the National Theater of Korea during the Young Theater Festival. Designing the lighting gave me a bad headache, and I got sick when we were setting up. It was hard, and I was terrified. But on the first day of the performance, I saw the stage light up with the touch of my fingertip…”

A small human being, with no religion, she said, “I saw the stage light up with the touch of my fingertip, and I felt the joy of having created a world.” Just like that, she was hooked.

But that couldn’t have been all. And I was right. There was a part two to her reason.

“After that, I had a chance to do lighting in the Munhwailbo Hall. There, I made a tiny mistake. But the lighting director berated me harshly, saying that ‘a kid who doesn’t even know the basics is working on lighting.’ That hurt my pride. Then, I learned about the year-long Stage Academy course at the Arts Council Korea. There, I met my teacher, Mr. Kim Chang-gi, and started learning about lighting.”

So, she found pride in putting food on her table? No. Actually, meeting Mr. Kim Chang-gi, the ‘Khomeini of lighting’, was more important. Choi said, “When I started studying lighting systematically, I started seeing a clear path in what I’d been doing without knowing.”

Choi Boyun currently belongs to a team called Stageworks, which has an office in Daehangno, Seoul. Since she’s not affiliated with a theater of a theater troupe and doesn’t receive regular wages, she is a freelancer. Founded in 2005, the name ‘Stageworks’ (although centered on the lighting team) contains the founders’ intention to work together with the stage and sound teams to do everything they can on stage. Today, Stageworks consists of 16 lighting designers.

There are three generations of lighting designers in Stageworks, including the Kim Chang-gi generation, Choi Boyun generation, and her students. As a result, there is a definite order of hierarchy, but all the members are like a family in that they are in the same occupation.

“One difference between Stageworks and other teams is that we only accept those who ultimately want to be lighting designers. So people have a strong sense of belonging, and there is also a huge pressure for everyone to study. Once you become a member of the team, you don’t become an assistant—we help you become an independent lighting designer.”

I was reminded of the four-character idiom ‘sucheojakju (隨處作主)’, that was popular in politics a few years ago. It means “Always be the master”, or “Act like the master wherever you go”. That’s the way Stageworks trains its members. And at the forefront is the successful lighting designer Choi Boyun. In her opinion, what makes her a good lighting designer?

“My personality. I concentrate on things quickly, and I shake them off quickly when I realize that’s not what I want. No matter how well you design lighting in your mind, everything changes on stage. Sometimes, there are other plays being performed in the theater where we have to set up for the next day. Actors can rehearse elsewhere, but we can’t. Being a lighting designer means that you have to invest time the most right before the performance. It’s like cramming for a test, and that works for me, too.”

But personality isn’t everything when it comes to work.

First, you need skills. Her knowledge of computers helped a lot.

“Lighting involves computer programming in an electronic device called a ‘lighting control console’. Usually, they’re made in the US or Germany, but in any case I’m good with machines. You have to simulate the position and angle of lights on computers. That’s easy and fun for me. Lighting is considered art, but it actually involves science before it goes on stage. I had this nagging thought that I was somehow lacking in art, because I’d studied science for so long. But my computer skills helped me overcome that.”

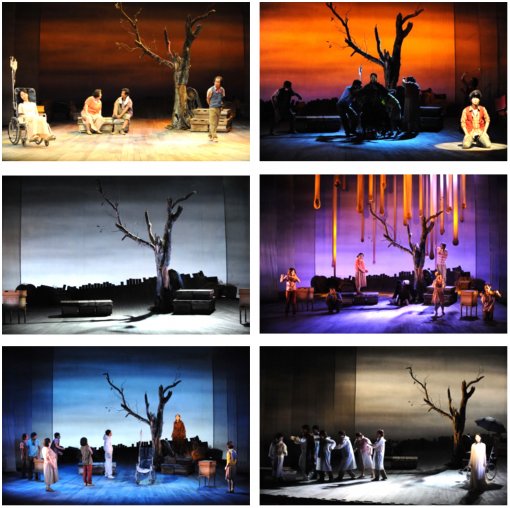

Invisible Man (a play by Son Hong-gyu) was performed at the Namsan Art Center from September through October 2014. A story about a family who plans to play a joke and treat the father as an invisible man on his birthday. But as the joke continues, the father begins to believe that he really has become invisible. The main themes of the play are family dissolution and alienation. The constantly changing lighting indicates the changing atmosphere in the house | Choi Boyun

Next is communication.

“A freelance designer needs to go and blend with the performing team. You can’t just do your part. There may be conflicts of opinion with the stage director. It’s easy to make a decision about lighting when you see it in theater, but it’s impossible to do that in the initial stage. So I take a number of samples, if possible, and explain. Sometimes I persuade the directors, but other times I get persuaded. When I see that my plan isn’t going to work, I let it go quickly.”

That doesn’t mean she accepts the directors’ opinions without question.

Five years ago, Choi designed the lighting for Mongran Unni (script by Kim Eun-seong, directed by Jeon In-cheol), performed at the Doosan Art Center in Seoul. She received great reviews.

“The lighting (Choi Boyun) was outstanding, as it opened and closed various spaces, dividing and reapportioning them. Fast scene changes and speedy progress of the story were impossible without the proactive lighting design. It is difficult to find plays with a more harmonious ensemble of directing, set design, and lighting design teams…”

— Kim Mi-do, stage art critic, Korean Theatre Journal, Summer 2012, in the pamphlet for the rerun of the performance from March 28 to April 22.

I came to reconsider the role of lighting from this review, where Kim said the lighting created and erased spaces, and also determined the pace of the play. The thought never even crossed my mind, but I readily accepted his assertion, thinking “That’s possible”.

If that was the kind of review you received, it’s probably safe to replicate the lighting for the next run of the same play. However, Choi changed the lighting design for the rerun, even though the performance will go on in the same theater by the same director and the same set designer (Yeo Shin-dong).

“I thought about a lot of things, while working on Mongran Unni the second time around. Before, I only thought that I need to do whatever I can to get my work done. So I used a lot of decorative stage lighting (lighting that is not necessary but used for demonstrative purposes). Even when directors didn’t request it, I thought I should. But these days, I think ‘I want to do this well’ instead of thinking ‘I should do whatever I can to get it done’. I keep on thinking, ‘Do I really need this light? Is it necessary?’ If I become complacent and settle at this level, I feel like this would be the end.” She then added, “Thank you for asking me what I’m thinking about these days.” It seems that she was focused on the changes for the rerun of Mongran Unni. Although it seems like a big cliche, I understood what she was going through as growing pains to become a better lighting designer.

And what came out of all her thinking was not ‘addition’ but ‘subtraction’.

“I thought the lighting was too much in the first two runs of Mongran Unni. This time around, the actors are having fun, but I also wanted to show the cold hard world that Mongran was experiencing. When an actor enters the stage, lighting designers often feel the compulsion to throw a light on her, but in this performance there are instances of actors performing in darkness.”

Choi meant that she changed the atmosphere of certain scenes by “subtraction”, or minimizing the use of unnecessary lights, and I think I understood what she meant when I watched Mongran Unni. The reason I can’t say I definitely understood what she meant is because I haven’t seen the previous performances and therefore I can’t tell the difference.

Does the lighting team have enough opportunity to communicate with the director?

When I asked her this, Choi mentioned the late Kim Dong-hyeon, former president of Theater Company Elephant Manbo.

“I had the impression that he was a cold person at first. But he was really funny. I met him through the play A Nice Person, Mr. Cho. We had a late night technical rehearsal, and Director Kim took the mic and put on a one-man show for us, playing every role himself, for the lighting rehearsal. It was really funny and cool, and I laughed so much. Director Kim called me his yeonu (演友), meaning ‘a friend bound by plays’. I always felt as though I was ‘learning’ when I was with him. And the pleasant memories of him is the power that helps me going.”

Of course, Choi mentioned a number of other directors. Then she said, “Before, it wasn’t the lighting designer that was afraid of the director, but the other way around. But now, there are more and more stage directors who are interested in lighting, and even the actors are trying to share their ideas on lighting design, and I welcome that.”

What kind of changes are occurring in the world of lighting these days? Choi pointed out the development of devices and technology, specialization, and the emergence of new territories.

In terms of the development of new devices and technology, she referred to the increased use of moving lights, that weren’t used much even in the early 2000s, and the replacement of filament lighting by LED lighting. While filament light bulbs produce warm colors, LED light bulbs emits cold colors. Choi said that the lighting designers’ personality and skill were now determined by the way in which these two different types of lights are mixed.

Specialization refers to the fact that lighting is becoming divided and specialized into different areas—plays, dances, musicals, and concerts. Compared to plays, musicals and concerts use many more lights. Moreover, lighting for concerts tends to be more spontaneous than rehearsed. And therefore it is difficult for one person to cover everything.

One of the new areas that emerged in plays is moving images. Plays didn’t involve video clips, and in the rare cases where video clips were used, they were for auxiliary purposes. However, they are now becoming important part of plays. That is why people are saying that we are now in need of the collaboration of stage, images, and lighting. In the larger frame of things, it seems that the development of technology is spearheading the transformation of stage.

In these changes, do you feel the need to lessen your workload and focus on studying? I asked her this question, based on my simple logic. But the answer I got from her was unexpectedly strong.

“On the contrary, I have to work even more. When I work, I try new things, and what I learn from that helps a lot. So I plan on working and thinking about all this.”

When I asked her about her income, she said, “I think now I earn enough to make a decent living.” She added, “I want younger lighting designers to have hope.” But she also didn’t forget to explain the conditions.

“Perhaps I’m okay with what I make because I’m not married, and I don’t have kids. I also worked on a lot of small performances that weren’t much money, and I can invest my time into my work anytime. But it will be hard on men.” In any case, she mentioned younger lighting designers. What kind of example would you like to set for them?

“Someone who motivates them. I want to be their role model. I ask them about what they do on their off days. Since this work is physically demanding, they often say that they just rest. I tell them to study. Freelancers can’t hide behind someone else. They’re only judged by their work. If they don’t do it well, they don’t get work the next time.”

Choi also fosters future lighting designers. Currently, she teaches lighting at Howon University, Hanyang University, and Dankook University. In the past, she taught at Kyonggi University, Dong-ah Institute of Media and Arts, Mokwon University, and Kyung Hee University. She makes enough to make a living, but not enough to save. She said that she sends all the money she makes from teaching to her mother, who is putting it all into a savings account for her.

Speaking of her mother, I asked her about her parents.

“When I said that I’m going to study theater and film, they knew how stubborn I was, but I think they were still a bit skeptical. When I actually passed and got in, they were very disappointed and worried. I had a chance to work at the Keochang International Festival of Theatre after graduation, and my parents came to see it. It was an outdoor stage, so they could see me working from the outside. After about half an hour of watching me, they came to me and said, ‘You’re not working under someone?’ I think that’s when they started to warm up to me.”

She wasn’t the only one who disappointed her parents. Choi Boyun only has one younger sister (39), who is also a lighting designer, although she works on concerts. You might assume that Choi had a big impact on her younger sister, but in fact her sister became interested in lighting design separately to Choi. She was working at some company, then decided to take a course on lighting at a private academy, and became a lighting designer. They both started working in lighting around the same time. Choi said that they help each other out a lot (perhaps their parents have no one but themselves to blame for this lighting DNA in the sisters).

“My parents love their children so much that they took a step back and let us do what we wanted to do. They moved to Chungju to take up farming. My sister and I got to do the lighting for the 40th anniversary concert at the LG Art Center for the singer-songwriter Choi Baek-ho recently, and we sent our parents tickets to the concert. They were happy to be at the concert, but happier to see us working at the lighting control console.” “

Perhaps it’s better to say, “We were happier to see our parents happy to see us working together.” Choi believes that lighting is important as her job, but being a daughter in a family is also important. Recently, she found the joy of traveling abroad with her sister and her parents. It seems that ‘family’ is the best light for her.

Bees, performed at Myeong-dong Art Center in October 2011 is a story inspired by mass bee deaths. People gather to find the cause of the death of bees and end up revealing their own pains and sufferings. Through lighting, Choi tried to convey the flow of time on the stage, which was decorated as the top of a hill in a rural village | Choi Boyun

One digression. Choi studied Japanese and now she interprets for theater staff from Japan. And she can also watch Japanese TV shows. She loves to watch owarai, or a form of Japanese comedy characterized by two commedians working as a duo. It is similar to mandam, where two performers trade jokes, like Jang So-pal and Ko Chun-ja, or Seo Yeong-chun and Ku Bong-seo. Although mandam involves theatrical aspects, it was rather unexpected to hear that someone who was once into the extravagant performances of the Takarazuka Revue is also into traditional mandam.

Choi received the Stage Art Award for Lighting at the 34th Seoul Theater Festival in 2013, and the Staff Award for Lighting at the 3rd Person of Theater Awards at the Seoul Theater Festival in 2016. But she is still growing. What kind of lighting designer does she want to be?

“I always say that I’m going to make sure that people I work with never work with other lighting designers again, that I’m going to make them fall head over heels. Lighting isn’t something where you do one great work, receive one big award, and are done with it. I want to be a lighting designer, whom directors talk about, saying ‘I really want to use her lighting in my work.’”

But she doesn’t want to be stuck with the label ‘Choi Bo-yun style lighting’.

“Once, someone told me, ‘Your lighting is charming and neat.’ I was really annoyed. How dare she define the many ideas in my head with just one word!’ Of course, it’s impossible for my lighting design to not reflect my personality, but I want to erase my personality from my work. I want to be a lighting designer who can make bold lighting design bolder, and detailed lighting even more detailed. I think I’d get mad if someone saw my work and said, ‘Oh, this must be Bo-yun’s work.’”

This shows Choi’s professinoal desire to design optimal lighting for each work, space, and time. This is the attitude she has when working, and she is respected accordingly. But she is not arrogant.

“Lighting is evaluated not by itself but within the performance. And I believe that’s right. As an audience, I never only looked at lighting either. Lighting is something you don’t really notice but has a huge impact on performances.”

“I can’t create light, but I can bring light,” she said. But I beg to differ. Choi creates light. Shoemakers cannot make leather, and clothes designers can’t make the fabric. They are only evaluated for the shoes and clothes they make. The same goes for lighting designers—the lighting they produce is their creation, and they are evaluated for that.

Even though I say all this, I feel bad because I don’t know much about lighting. This interview would have been better had I more knowledge and experience with lighting (not that I know much about directing or acting either).

In a different interview, Choi was asked, “What do you think is the role of lighting in plays?” She gave a great answer. And I would like to close this interview with that.

“I think it’s a closing pitcher.”

That’s right. The closer may not be the winning pitcher, but, in order to hold onto the lead, you need the closer. Choi is working on her ideas in front of the lighting control console, ready to go out into the field when she is needed.

CONCERTS: Hyukoh Concert [23]; 2017 Kim Kwang Min Concert; Choi Baek-ho’s 40th Anniversary Concert; Lee Juk’s Small Theater Concert [Stage]; Yuki Kuramoto Concert; Han Seung Seok & Jeong Jaeil – Bari [abandoned].

AWARDS: 2013 – 34th Seoul Theater Festival, Stage Art Award for Lighting;

2016 – 3rd Grand Seoul Theater Awards, Staff Award for Lighting; 2017 – 54th Dong-A Theatre Awards, Stage Art Award.

Have a question for the writer? Send us a mail or sign up for the newsletter.

More at The Dissolve

- Magazines focused on alternatives—Womankind and New Philosopher

- Why Rainbow Cake Architecture?

- "Science is changing people’s view of the world, but aren't the humanities lagging behind?"

- Shin-Kori 5 & 6: Nuclear twins born out of a wrong question

- Playwright and director Choi ZinA: “Uncomfortable? Unfamiliar? Then I’ve done my part.”