— 50- and 60-year-olds are burdened with supporting their adult kids, due to low growth, unemployment, and late marriages

— In Japan, younger generations are beginning to shoulder the ‘double care’ burden

Park (58), a consultant, visited a bank during work hours. Her daughter, who works at a small firm outside of the Seoul area for KRW 2 million a month, had called her to say that she doesn’t have enough to pay the rent. “She finally found a job when she was around 30, so I thought I’d be free from worrying about her,” Park said. “But she said she wants to change jobs and would like to study for the TOEIC but didn’t have enough money. So I regularly send her money for her lessons and for some of her rent.” In the previous year, Park invited her father-in-law, who is in his 80s, to come live with her and her husband. “After my mother-in-law passed away, I thought he’d be lonely by himself, so we asked him to live with us. But it’s been difficult,” Park said with a laughter. Then she added worriedly, “My husband and I are working hard to save up for our daughter’s wedding, but I don’t even know if we’d even be able to get some pocket money [from her] in our later years.”

Double care? Now it’s triple care.

According to the apartment rental website ABODO on March 24, 2017, the number of ‘Kangaroo children,’ who remain in or return to their parents’ homes, has been on an upswing. Adult children who currently live with their parents account for 34.1 percent, and of them 9.2 percent are unemployed. New university graduates who started working are found to be living in their parents’ shade in order to pay back their student loans and save on living expenses.

With rising numbers of adult children relying on their parents for economic support due to youth unemployment, late marriage, and low economic growth, the financial burden is falling on men and women in their 50s and 60s. Naoko Soma, a Japanese professor, has called this burden ‘Double Care’—the double responsibility of caring for older parents and adult children. Last December, the Mirae Asset Retirement Institute conducted a survey of 2001 men and women aged 50-69 with at least one adult child and at least one parent or parent-in-law. Of these, 34.5 percent (691) were in double care situations.

On top of this has emerged ‘triple care’: some parents even have to care for their grandchildren because their own children are dually employed with kids (DEWKS). According to the 2015 Shinhan Bank Report on Average People, which surveyed 20,000 Koreans, while some triple carers receive money from their children, the majority receive no financial compensation at all. The average period people in their 50s and 60s spent taking care of their grandchildren was 26.5 months, which was longer than the average period they spent taking care of their elderly parents (22 months).

Underneath this phenomenon are overly-controlling parents. Those in their 20s and 30s today grew up with a lot of attention from their parents. The baby boomers who were busy working and surviving in poverty after the Korean War were strongly determined not to hand down poverty to their children. As a result, compared to their own parents they were more interested in all aspects of their children’s lives, including their education and lifestyle.

Heo Du-young, the CEO of David Stone, said, “People in their 50s and 60s, who are baby boomers, invested a lot in their children. As a result, even after the children grow up and start working, they require their parents to be mentors who they can communicate with horizontally, and rely on them.”

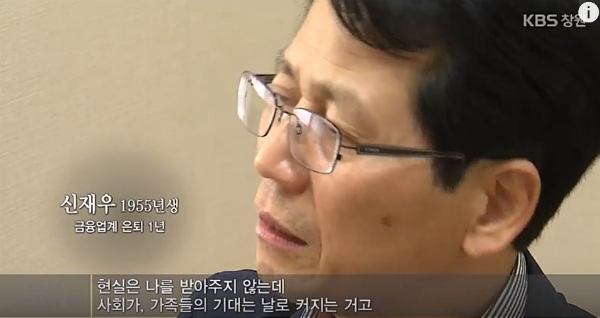

A retiree talking about his circumstances on a KBS documentary. People in their 50s and 60s have devoted themselves to their families in their youth and are now shouldering the burden of early retirement, children’s education, and caring for their parents. They face a high risk of depression | KBS/The 100-Year Life for Baby Boomers, Finding New Hope after Retirement

Low economic growth and high youth unemployment rates are two of the factors that delay adult children’s mental and financial independence. In the 1980s and 1990s, when Korea’s economy was growing exponentially, parents only needed to raise their children and let them go when they came of age. The economic growth rate at the time was 9.8 percent, while the youth unemployment rate was merely 5.5 percent. Anyone who tried was able to find jobs.

In contrast, to those in their 20s and 30s today, finding a job can be murder. Last year’s economic growth rate was 3.1 percent. The average for the last five years has been around three percent. Meanwhile, youth unemployment is soaring. At the end of the first quarter in 2017, the unemployment rate for young people (between the ages of 15 and 29) rose to 11.3 percent. The expanded unemployment rate, which includes potential workers who did not look for work, was 24 percent. Of every ten young people, 2.5 are unemployed. In 2000, 82.1 percent of Korean youths were not married; the figure rose to 94.1 percent after 2015.

Children who do not gain financial independence when they come of age become a headache at home. Lee (27, Seoul resident) has been studying for the teacher certification exam for four straight years now and lives with her parents, who are in their 60s. She has been planning on moving out as soon as she passes the exam, but has not been able to. “On days when my parents tell me to look for a job instead of studying for the exam, we end up arguing,” she said with a sigh. “Our relationship has been strained, so I’ve been looking for a small studio to move out to, but I have no income. Now I study at the public library in town and go home late to avoid my parents.”

Song Shin-young, a financial consultant at A Plus Assets, remarked, “In the past people were considered old when they reached 60, but life expectancy has risen by 20 to 40 years. As a result, parents who have devoted their lives to their children’s education rather than saving up for their retirement are feeling burdened. The children have reached the age to start spending on consumer goods, but their lives are tough because of the highest unemployment rate in history and low economic growth. So the parents can’t even rely on their children to take care of them in their old age.”

We need a macroscopic discussion on care burden

Experts predict that care burden is not a problem solely for the baby boomer generation. Unless the socio-economic structures improves, the next generation will face the same burden. Therefore it is important to raise awareness of this crisis.

Having experienced the phenomenon of late marriage before Korea, Japan is already making preparations for citizens in their 50s and 60s. In Yokohama, a counseling station was established to figure out and address the types of difficulties that surround double care. Despite the preparations, the situation has been worse than predicted. The average age of people trapped in double care situations has fallen to 40-49, and it is expected that those currently in their 30s will also have to shoulder the double care burden in the future.

Yun Chi-seon, a researcher at the Mirae Asset Retirement Institute commented, “(The situation in Japan) is not a unique phenomenon. Double care did not emerge because the people in their 50s and 60s wanted to care for both their parents and their adult children. Rather, it was the macroscopic environmental changes of low economic growth and life extension that drove people into this situation. If we can’t avoid the trap of double care, we need to look for ways to lighten the burden.”

He added, “Korea lacks the support system for childcare and nursing care for older people despite the rapidly ageing population and delayed marriages. The social cost of the care burden can instigate intergenerational conflicts, so it is necessary for us to continuously conduct discussions, reach a public consensus, and establish care burden policies at the national level.”

Have a question for the writer? Send us a mail or sign up for the newsletter.

More at The Dissolve

- The rise of web novels — Is genre fiction the way forward for Korean literature?

- The mind behind BTS on balancing artistry and business

- Women are half the population but most newspaper sources are still male

- The psychology behind Kakao Talk profiles: What's your ego-state?

- Defence minister criticized over remarks on Pohang helicopter crash