Brought to you in partnership with Book Club Origin.

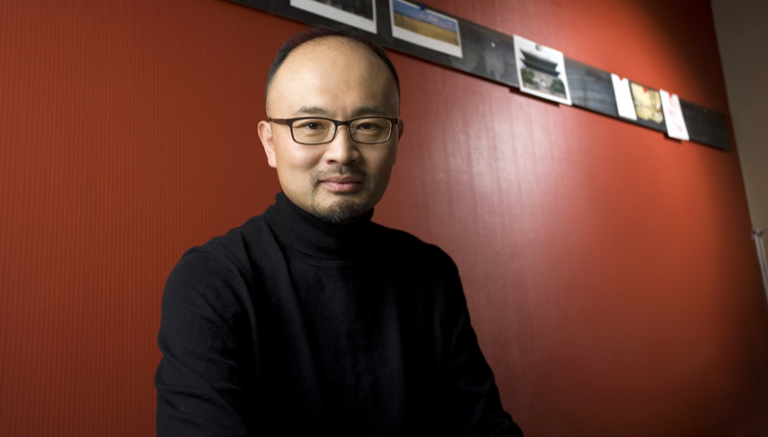

The architect Hwang Doojin has expressed a steady flow of architectural ideas and opinions over the years.

Three years ago, he proposed an alternative idea to Korean urban architecture in his book Rainbow Cake Architecture.

As an extension of those ideas, he went on to visit and research architecture in parts of various Korean cities and share the results in a book titled The Most Urban Life.

In this piece, I’d like to present to you his talk at Open House Seoul 2017 last October titled “Discussing Commercial-Residential Apartments”, as well as the Q&A session held after the lecture.

His perspective made me think about aspects of urban architecture that I hadn’t paid much attention to: Why were hanok (traditional Korean houses) not multistory? What is the relationship between hanok and apartment buildings? What is the problem with apartment complexes? How were the brand-name commercial-residential apartments born?

Hwang Doojin

From hanok to apartments

I’ll be talking a lot about Seoul mainly. Before getting into the heart of the matter, let’s first look at two maps related to the talk.

The first map is of Seoul, and I’ve colored the buildings featured in The Most Urban Life. Different colors represent different years. Of course, I didn’t talk about all commercial-residential apartment complexes in Seoul, so there is a limit to the size of the sample. But even taking that into consideration, you can see that most commercial-residential apartment complexes were built in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Most Urban Life by Hwang Doojin | Banbi, Korean only

The next map is one in the book. I classified the commercial-residential apartments into three groups: first is a single commercial-residential apartment building, and there are commercial-residential apartment complexes and mall-type commercial-residential apartment complexes. This map shows the different types of apartment buildings by color.

The difference between this map and the previous one is that you can see the geographical features in this one. Mr. Shin Yun-seok, who created this map for me, mainly works on map and chart graphics. But he’s been trained in architecture, so he not only uses data but also analyzes them.

When he was creating this map, he suggested that we put in geographical features. When I saw the map with all the geographical features and the locations of the commercial-residential apartments, I realized that there were certain common aspects.

A considerable number of commercial-residential apartments were located at the foot of the mountains—where the plains met the mountains. This means that they were closer to waterways, and a substantial number of buildings that I’ll be talking about today have been built on waterways.

Rainbow Cake Architecture by Hwang Doojin | Medici Media, Korean only

I’d like to talk briefly about how I went about writing this book. In my previous book, titled Rainbow Cake Architecture, I discussed the genealogy of rainbow cake architecture built in Korea briefly in about two or three pages. But there were many people who were interested in that chapter, and The Most Urban Life is the result of that short chapter turning into a 520-page book.

So why did I write this book? When I looked back, as an architect and as a writer, I’d written about The Return of Hanok and I’d been working on hanok professionally. My thoughts on cities and urban architecture followed each other closely, and I think that’s how the book came about.

Hanok is an architecture that is paradoxically an antipode of commercial-residential apartments and rainbow cake architecture. Simply speaking, I believe the two most important keywords in understanding cities are density and complexity.

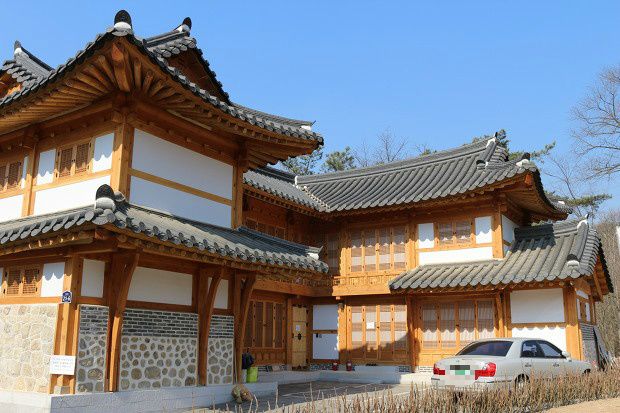

Hanok was not an architecture with strength in those two aspects. It is a great and cherished cultural heritage for Koreans, of course, but from the perspective of urban construction, I learned that hanok had too many limitations through working on it.

Bukchon Hanok Village

I’ll start with the story of the sadaemun (“four great gates”) of Seoul. Although it varied by time period, the population of Hanyang in late Joseon Korea was about 300,000 people. Currently, there are less than 270,000 people living within the sadaemun. We can say that we’ve returned to the Joseon era population.

When you look at these buildings, you can see that basically all of them are one-story buildings. One of the concepts used to calculate urban density is the floor area ratio. In Hanyang, the floor area ratio was only about 30 to 40 percent of what it is now. That floor area ratio isn’t for what we would now call a city. It’s just a village. A big village.

But after the Japanese colonialization, the Republic of Korea was founded. And we didn’t leave this medieval city with ultra low density but kept Seoul as the capital city. Since then, the area of the city increased over five or six fold, and the population grew to 10 million—25 million when you take everyone in capital area, including Gyeonggi Province. It has now become a global mega city. So then what happened to the future of the city that had once consisted of hanok, and ultra low density architecture?

This is a picture of Anam-dong I took in the early 1980s, when I was a sophomore in college. In the 1940s, when tram routes that ran outside the sadaemun were installed, large-scale residential complexes began to be formed outside of them. You’ve probably all heard of Bukchon, Seochon, and recently Eunpyeong hanok villages, but you probably didn’t hear about Anam-dong Hanok Village. The reason is simple. It’s not there anymore.

Eunpyeong Hanok Village

You can interpret this in different ways. You’ll definitely hear the whole “Koreans must not love their history, culture, and tradition. Hundreds of years old buildings are well preserved in Europe, so why are Koreans…” Prior to the advent of the automobile, Europe had already created high density cities with an average number of six stories per building, which was enough for the cities to turn into modern cities. So it’s impossible to compare Korea and European countries.

Then there are people who say, “Well, it’s hanok’s fault.” They argue that people should’ve developed four or five-story hanok in the Joseon dynasty. So why didn’t we? Because Joseon Korea was a country with the traditional four classes (scholars – farmers – artisans – traders). Joseon was fundamentally an agricultural country, and thought little of commerce.

How could the economy grow in a country like that? So we didn’t need high-rise buildings or high density cities. At the time, people were probably able to lead sufficiently comfortable and luxurious lives, in their own ways.

What I’d like to emphasize is the latter. Cities are places where density and complexity are of utmost importance. But we didn’t have a grasp of the concept of density that is required to understand cities, and many times we considered high density a sin.

It’s like how we were physically in cities but we yearned to be in the countryside. One of the reasons for that is that up until my generation, a lot of us were not originally from cities. Most of the urban population consisted of people who weren’t originally from cities, and even if they were from cities—and even now when you look into it—only a few of us have actually had the true urban experiences.

A glance at the architecture community shows that much discourse about population is related to land, in particular. And this concept of land isn’t often that of “artificial land” but of “natural land”. These are all legacies of the agricultural age. This old world cultural idea still has a big influence on how we look at cities and architecture.

So what emerged as a solution is the apartment—specifically, the apartment complex. The more apartment complexes that are built, the more likely cities are to become isolated islands. This three-dimensional image shows the well designed landscape. They look wonderful like Le Corbusier’s islands in a sea of green.

But in reality? When apartment complexes are built, people who do not live in the complexes are unable to pass between the apartment buildings or through the complexes. Because the complexes turn the whole area into so-called bolted communities.

To make it worse when they begin to build they make the basement into a parking lot and make the ground higher than it was originally. The result is the ground floor is 1.5 meters higher and we walk past a wall, not the building, which is different from the original blueprints.

Rainbow cake buildings

A piece of rainbow rice cake (mujigae-tteok) | Shutterstock

There doesn’t seem to be anything especially attractive about cities, but you notice certain areas that people like to visit. These areas haven’t been planned that way, and they aren’t necessarily filled with beautiful buildings designed by famous architects. But artists flock to these areas, the number of coffee shops rise, and you sometimes see gentrification.

What do many of these areas in Seoul have in common? They are areas with a lot of rainbow cake buildings, with commercial facilities in lower stories and residential areas in higher stories. Major examples are Seochon, Gyeongnidan-gil, and Honda and surrounding areas. There is a balanced mixture of commercial and residential facilities in the buildings that are not too high or low.

Gyeongnidan-gil

But it turns out all of the cities across the world are made up of buildings like these. Italy’s Milan and Bologna, Manhattan, Paris, the district behind the Sydney Opera House, Singapore, Malaysia’s Kuala Lumpur, and Bankok in Thailand are all the same. People live in buildings in the center of the city where the lower floors are occupied by shops and stores.

There are way too many examples for me to list. Do you know anyone who lives in a stand-alone house in Manhattan or in Paris? Can you even live in a stand-alone house in Manhattan? Not even Trump can live in one. Why do people believe that we need to live in stand-alone houses in cities?

Of course, there are special exceptions, but in our minds, ideal residences tend to be stand-alone houses or apartment complexes. Not because we like apartment complexes, but for other economic reasons, like that it’s easier to sell and purchase.

Casa Mila

Casa Mila, built by Gaudi, who is known for his artistic ego in the architecture community to the point of being called the ‘crazy architect’. This building is also a commercial-residential apartment. The two lower stories are for shops and stores, and the higher floors consist of about 40 apartments. We go to foreign countries, looking at such architecture, but why do we talk negatively about the population density of our cities? Why the double standard?

Seoul is not a high density city

Seoul might look like a high density city, but it’s not. The average floor area ratio in Seoul is about 160 percent, compared to the average floor area ratio in European cities such as Barcelona or Paris, which is about 250 to 260 percent. You might ask, “How is that possible when there aren’t many high rise buildings?”

Just as we have recently, and painfully, realized that society does not become affluent with an increase in the number of affluent people, it is not important to raise one end of the normal distribution in order to raise the average. You have to raise the middle section. It’s the same for the average urban density. The number of high rise buildings does not affect the average urban density.

Korean cities are too horizontally expansive. As a result, Korea has become a society with the longest commuting time among OECD countries. There are many different factors that determine the quality of life of the members of society, but in my opinion one of the most important factors is the amount of time one can have to oneself.

Your own world. The world of obsessive indulgence. Or the world of the so-called otaku. There is no time for us to delve into and grow this world in a way that raises the level of culture or emotions in society. The structure of our cities do not allow for such time. This is because when Seoul was being developed, its areas and districts were modeled after American urban planning.

Several years ago, one of the presidential candidates left us with a thought-provoking slogan—”A life with an evening”. That’s what we need. That’s how our society can move on to the next stage. So then, is there a solution to make this happen? This was the reason and the process that led me to ask the question that prompted me to write a book.

I’m not saying that rainbow cake architecture is something that only I can do or talk about. I came to write the book because I wanted this type of architecture and the discussions on urban residence to be more widespread.

Korea’s earliest rainbow cake buildings were hanok shops

So now, let me get into the main points of the book. What, in our city, can be considered the earliest prototype of rainbow cake architecture in our society? We can trace that back to “hanok shops” that were based on taverns (gaekju) in the late Joseon dynasty.

There are many old shops, particularly in the old downtown area of Seoul, that are attached to private residences in the back. Although these types of residences are not enough to bring density into the conversation, I believe that these may be the first instances that allows us to talk about complexity.

Then about a century ago, changes in population density occurred. After the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1876 was signed, various multi-story building designs in Japan, which had modernized early, began to come into Korea. Korean merchants who saw the designs attempted to build a multi-story building within the traditional architectural system and the result was the two-story hanok shops. Just looking at the Joseon dynasty, the emergence of these two-story hanok shops was, in my opinion, the most amazing thing that happened in the history of Joseon architecture.

You’d think that in two-story hanok shops, the owners would have used the first floor as a shop and lived on the second floor. But in fact, both stories were used as shops. It’s because Korean houses required ondol [underfloor heating], which could not be installed on the second floor or a wooden building. So then where did people live? They lived in the residential hanok located behind the two-story store building.

There are only a few of these two-story hanok shops left today, to the point that renovating instead of destroying one of the last few hanok shops on Namdaemun-ro became big news.

A two-story hanok store-residential building in Okin-dong | Hwang Doojin

As commerce developed even more and the urban density rose, two-story buildings weren’t enough. So then what happened? These two-story hanok were destroyed, and bigger buildings were built. Higher ones. Ones that were built with bricks and concrete.

What happens to the residential hanok behind the store building? The floating population increases, since the area becomes a commercial district. So people leave. This is a good example that shows residences and commerce cannot exist on a horizontal level. This is Insa-dong. Or more accurately, it’s Gwanhun-dong, but overall it’s called Insa-dong.

So what happens to these residential structures? People put roofs over the yards. And they become Korean food restaurants. A considerable number of Korean food restaurants in the old downtown Seoul had been originally connected to two-story hanok shops.

Even in Southeast Asia, which is closer to Korea, the urban structure is completely different. There are many shophouses—three-story shop-residential buildings. There are still many of them left. There are the shop-residential buildings in the old town plaza of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and in Singapore’s Chinatown.

I visited the Chinatown Heritage House, which is part of an old shophouse in Singapore. When I asked if the building was an original, the official there said yes. The reason I asked that question was because the building was a concrete structure. This means that a concrete shop-residential building was built because concrete was available at the time.

Chungjeong, Korea’s first apartment building (1930), is (now) a rainbow cake too

Now, let me get into apartments. I should’ve introduced this one first, because this apartment building was built earlier than the hanok shop in Okin-dong or Gwanmun Building in front of Seoul Station. In Korea, the Republic of Aparment Complexes, we cannot but ask about the very first apartment building built in Korea.

The (current) facade of Chungjeong Apartment Building | Hwang Doojin

According to my research, it seems that there has been an intense debate on the first apartment building in Korea in the academia. It seems that Professor Park Cheol-Soo at the University of Seoul put an end to this debate. Toyota Apartment, built by a Japanese man named Toyota in 1930, which was later renamed as Yurim Apartment and now Chungjeong Apartment. This Shrek green building standing back to back against the plot of the French consulate in Korea is the very first apartment building in Korea.

Look at the first floor of this building. There are shops. Of course, it’s impossible to know whether Chungjeong Apartment started off with shops on the first floor, since it’s not easy to look for documents on the building from the colonial era. If it was built that way, then it is the first commercial-residential apartment building in Korea. I put it in my book because it functions as a commercial-residential apartment building now.

The bus in the picture is not in motion. There is a bus stop right in front of the apartment. It must be really convenient for the residents, right? The only thing is that with the expansion of the Chungjeong-ro, the front part of the building was actually destroyed. The current facade of the building you see in the picture is after the building’s front part was cut off and destroyed. Prior to the 1930s, there was a part-government, part-private company that supplied residential buildings, called Dojunkai, which was established by Japan in Korea. The roof of the apartment building looks similar to the Japanese-style apartment buildings the company had built.

There are a lot of urban legends at Chungjeong Apartment Building. People say that there used to be a North Korean military court and massacres occurred in the building. I’d asked people who studied military history, and they told me that in the military history field there is no information related to Chungjeong Apartment. So it seems that the urban legends are only half-truths.

There is a well known story related to the Korean War. It’s about the picture that Max Desfor, an AP war correspondent, took. This picture was taken sometime around the time the Korean Army recaptured Seoul. A US marine is looking at a North Korean soldier who had been hiding in a manhole burned to a crisp. There are only a few pictures of the war that contain the people of the two sides together. The building in the background is the Chungjeong Apartment.

Photo by Max Desfor, AP

When you look at the picture, you can see the facade of the Chungjeong Apartment before it was cut down due to the expansion of Chungjeong-ro. The Chungjeong Apartment is a building with a number of stories, so it’s worth remembering. When you see it in real life, the building is rather old and sad.

For your reference, it’s difficult to go see these apartments in Seoul. Most apartments aren’t very friendly. The buildings are old and people don’t like others coming to take a look. There are notices, warning people that taking photographs of the building will result in a lawsuit. I took these pictures while apologizing in my heart. And most of these apartments are split between people who want the building renovated and people who oppose them. As a result, renovations don’t happen so easily.

These pictures don’t look like much, but I took them on top of the subway station vents in order to get a better view at this height. I took most of the pictures that are in my book.

The reason being, I couldn’t go to see these apartments with other people. Even just a group of two or three attract attention, so you have to go alone. I know several great photographers, but for the efficiency of the project, I had to go alone.

Look at the entrance of the apartment building. There are three signboards. When you walk inside, it has a courtyard. It was the newest apartment with central heating and air conditioning, so there are chimneys. This is the image of the interior of the apartment. Behind it is the courtyard. This whole area is a redevelopment area, and this picture was taken from there.

Now, when you look at the outside wall of the building, it looks like paint. It’s paint on tiles. Since the history of Korean apartment buildings began in the 1930s, it’s only been about 90 years. But the one thing that did not change is the material for the building exterior. Put cement on concrete, then paint, and that’s it! It can’t get any cheaper! Our society has been using the cheapest material to provide housing for most of the people.

Jwawon Sangga and Sewoon Sangga were the Tower Palaces of the 1960s

The next is the Jwawon Sangga, built in 1966. When I visit these buildings, sometimes other people contact me to let me know of other such buildings, and sometimes I look them up online. The whole process generally involves… When I can find pictures or when someone lets me know, then I have a great ally: street view. So I go online and check it out first. But when you look at a building like this one, would you want to go? So I think, “The building looks too…” but I gather myself together and think that I should at least go see it in person.

When I do go visit, these buildings talk to me. “Hey, you came.” Well, actually since they’re much younger, they’re a bit more polite. “Sir, you came.” And I say “Why do you look so much older than your age?” Korea is a strange country. It has the longest lifespan for humans in the world but the shortest one for buildings. It’s a country where people take care of themselves but not of the buildings.

This building is right across from Gajwa Station. The first two floors are stores and shops while the third and fourth floors are residential apartments. I was glad that I went and saw this building. It’s actually a really big building that goes inside as well. It actually should be called a “commercial-residential complex”, but the building in Korea that has the honorable title of becoming the “first commercial-residential complex” is Sewoon Sangga.

But according to the building register, Jwawon Sangga was built a year earlier than Sewoon Sangga. When Jwawon Sangga was completed, Sewoon was still under construction. Before I visit these buildings, I get a copy of the building register. It’s like the family register for buildings. It tells you when it was born, how big it is, along with other characteristics. It also tells you the building’s parents—the owner, architect, and constructor. Well, it’s supposed to, but for most buildings those sections are left blank. So these are, pardon my French, bastards.

I looked at the building register for Jwawon Sangga, and it was approved for use on December 23, 1966, while the first approval for use for Sewoon Sangga was November 17, 1967. So why did we only talk about Sewoon and not Jwawon? That’s because of the awareness of the buildings. There’s a lot to talk about with Sewoon, and above all it was built by the Kim Swoo Geun group.

Look at the phrase on the advertisement. You’d be able to attract a lot of customers with that even now. “Modernization of life. Apartments for one-person households available for sale or rent. Steam ondol radiator for cold and hot water” … “Parking lot, 8 minutes to City Hall, sink, toilet, automatic fire alarm, first and second floors cleaned…”

I couldn’t find out who designed Jwawon Sangga. Buildings get sad when they’re anonymous or unknown. There had been a fire in the building, but it wasn’t properly restored. This is what the first floor corridor looks like. Both sides of the corridor are open. Looking at these pictures, you might say, “Well, that looks awful,” but take a look at this advertisement.

It was a luxury apartment at the time. I told people this when I went visiting these buildings, but we can’t judge these buildings by the shabby, dodgy, old exterior they have now. When they were first built, they were all Tower Palaces. Celebrities lived in these buildings, and high-ranking officials lived there as well.

It was probably the same for this building. Considering the location of Gajwa Station, I’m doubtful as to whether young single people lived enjoying the modernization of their daily lives here at the time.

Now we come to Sewoon Sangga. It’s one of those “hot” buildings now. We call it Sewoon Sangga, but including the Hyeondae Sangga, which is not there anymore, Sewoon Sangga consists of eight buildings. They were all built in different years and by different constructors, but it seems that they were all designed by the Kim Swoo Geun group.

Sewoon Sangga (Sewoon Electronics Market, south facade) | Hwang Doojin

Actually, architect Kim Swoo Geun didn’t seem to be involved with this project in depth. Architect Yun Seung-jung was more involved in it. You can find more detailed information online, since there seems to be a lot of information about Sewoon Sangga available these days. In any case, Sewoon Sangga is officially known as the “first official commercial-residential apartment complex in the Republic of Korea”. But in my book, I cautiously mentioned the possibility that Jwawon Sangga might be the first. I suppose the academics will prove it either way.

Personally, I believe it would be best to approach Sewoon Sangga not as a single construction but by finding common aspects of eight different buildings. Since it’s such a big complex, it’s difficult to show everything in just one picture, but I’ve got what’s important in this picture. And I think it’d be more effective to show you the image.

In photographs, Sewoon Sangga looks rather nice. There are tall parts of the buildings, and the axis of the building in the middle is gigantic. One of the buildings to the south of Sewoon Sangga is the Pungjeon Hotel, now PJ Hotel, and there is a basement in that building. Apparently the first supermarket in Korea used to be there. Aside from the street view function, another thing that I find helpful when visiting these places is the old newspaper search function on Naver. Of course, my colleagues, friends, and scholars are a great help as well.

From the beginning, it’s Sewoon Electronics Market, Chenggye Sangga, and Daelim Sangga. All three buildings have a courtyard in the center. Usually people think of a dirty old building when they hear Sewoon Sangga, but the interior was relatively fine. The PJ Hotel and Sampoong-Nexus Building in particular have been nicely renovated.

Courtyard in Sewoon Sangga | Hwang Doojin

Since the two buildings are actually in great condition, you’d find yourself confused if you think of Sewoon Sangga as just a bunch of old buildings. And the Seoul Metropolitan Government started the project of constructing the connecting walkways, so it became the icon of urban regeneration. This is the fate of a great building. I suppose that when you have a great father, you end up with a great fate.

Painstaking effort went into each of these shots of various parts of the buildings. To tell you something personal about these pictures, I tried to take pictures from the front facade rather than take perspective shots. Because I thought that was the most respectful way to express the buidlings. Like taking a portrait picture. I posted these pictures on Facebook, and a younger architect asked me, “How did you take pictures of these old buildings like idol singers?” That was the best compliment I received for these pictures.

Nagwon Building: “accidental modernism”

Next is one of my personal favorites and the last place in today’s visit: Nagwon Building. There is a lot to tell about Nagwon Sangga, so I need to cut everything short. The road it’s located on is Samil-daero. This road, simply speaking, is the backbone of Korea. Above it is Gwahoedong-gil, and it passes through the Board of Audit and Inspection and reaches the Seoul Fortress.

Nakwon Sangga on Samil-daero | Hwang Doojin

In other words, this road starts at Bukhansan Mountain, passes throguh Bugaksan Mountain, and connects with the axis of nature in Seoul. To the south, it passes through the First Tunnel, across Hannamdaegyo Bridge, and turns into Gyeongbu Expressway. So you can see how important this road is.

Even now, Nakwon Sangga is a great building. One, it’s big and it’s tall. There’s a musical instrument shop, a traditional market in the basement, and even a movie theater. And there are a total of 149 apartments from the sixth to sixteenth floors. You can imagine that someone designing this building had some kind of a theoretical vision or future in mind.

Someone presenting the theory that “Cities should have this kind of building”, and the so-called opinion leaders and policymakers of this society accepting it, leading to a social consensus or a type of movement, and a great architect who agreed with the idea designing the building. You might imagine something like this.

But when you look into it, the place where it was built was an air defense zone, which was created to protect the city from air raids during the Pacific War while Korea was under the Japanese rule. It was the same with Sewoon Sangga. And after Korea’s liberation, a traditional market was somehow opened there.

But the government needed to build the Samil-daero (road) here. Because around 1968, when Nagwon Building was built, the Gyeongbu Expressway was being constructed. Since Samil-daero is the backbone of Korea, of course, this road had to be paved.

But then there was the traditional market, the location of which could be considered the back of the neck on a human body. So the government began to negotiate with the Seoul Metropolitan Government. At the time, the mayor of Seoul was Kim Hyeon-ok, known as the “Bulldozer”, and the merchants of the traditional market handled it wisely. Interestingly, most of the merchants were landowners, so they founded the Nagwon Sangga Corporation to negotiate with Seoul.

Ultimately, the traditional market was moved to the basement, which is still there today. The first floor is the road, since Samil-daero had to pass through this location. The second through fourth floors are shops and stores, and the merchants of the traditional market have some of the shares.

Market in the basement of Nagwon Sangga | Hwang Doojin

So that was the design, and now you need someone to build the building. At the time, neither the Korean government nor private companies had money, so there was no one who could invest the money and construct the building. So Daeil Construction camee to build this building and received benefits. The deal was to build luxury apartments above the mall and allow the construction company to sell it.

So in the end, Nagwon Sangga has three owners: Nagwon Sangga Corporation, Daeil Construction, and a council consisting of the residents of the apartment. So when you gather all the real estate registers, they pile up high.

So the building wasn’t built with a certain vision. This big, complex, and unique building was created as a result of the process of the government and the private sector negotiating and struggling to make ends meet. In my book, I called this process “accidental modernism”. The building wasn’t built with modernism in mind, but somehow ended up that way.

Apparently, there were many different types of stores in Nagwon Sangga. Now, it specializes in musical instruments. When I visited Daeil Construction, I heard a funny story. They said Sewoon Sangga ultimately chose to be an electronics market, so they chose musical instruments, which was a much smaller market, and they think they were right.

Since the electronics market is big and changes quickly, it moved to Yongsan and finally online. Electronics couldn’t be contained physically within just one place. But musical instruments on the other hand could be handled within a big building. And that was how the building was reconfigured in the 1980s. Most of the musical instrument shops in the building are owned by Daeil Construction. All this is to say that Nagwon Sangga has a very unique history.

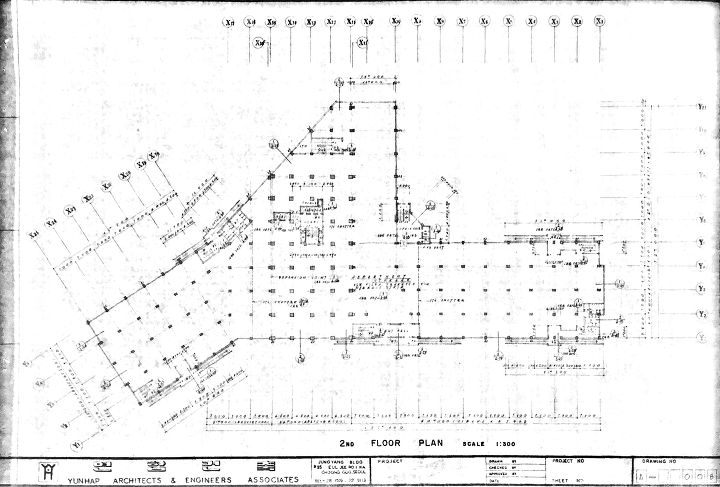

The original three-dimensional map and other important floor plans of the building still hang in the office of Daeil Construction.

A floor plan of Nagwon Sangga | Hwang Doojin

Strangely, there are a number of stories about the designer of the building. Some claim that Kim Swoo Geun was the designer, while others claim that it was designed by a Japanese architect. Some students still come asking if this was designed by Kim Swoo Geun, and when the company says no, they leave disappointed.

Isn’t that strange? They probably came because they’re interested in the building, so why does it matter who designed it? But there it is right there on the floor plan: Yeonhap Construction. It was a company located in Chungmuro at the time, and the CEO was Kim Man-seong. The designer of Nagwon Building is Yeonhap Construction.

A relief in a courtyard wall of Nagwon Sangga | Hwang Doojin

The more you examine the floor plan of the apartment building, the more you appreciate it. It’s well organized. The center of the plan is the courtyard. The famous courtyard of Nagwon Sangga. Those who came to explore the buildings today will have already learned it, but it’s very quiet, and there are two reliefs that seem rather religious.

It’s a bit tacky but isn’t it very upbeat? The reliefs were created by a laborer at the site. I jokingly wondered if he was the Korean Diego Rivera. I think it’s one of the most impressive spaces in the old downtown of Seoul.

Facade of Wonil Apartment | Hwang Doojin

Yujin Sangga and Wonil Apartments represent missed opportunities

There are two rainbow cake buildings in Hongje near one another: Yujin Sangga and Wonil Apartments. Yujin Sangga is amazingly long and big, and next to it is Inwang Market, the hub market in the northwestern part of Seoul. It’s a big market, and Wonil Apartment is actually one with the market. The main entrance to Inwang Market penetrates the first floor of Wonil Apartment as you can see. So it forms one body.

The elevation map shows how the building was well designed even though we don’t know who it was designed by. It’s well proportioned and has many great characteristics even compared to the ones that were designed by somewhat renowned designers. There is a courtyard in Wonil Apartment as well, although it’s proportions are a bit narrow. The canopy on the top is well designed. They put in glass, so that light could come through, and the sides are open for ventilation.

Had we continued to study and develop these architectural concepts, we might have ended up with something like Market Hall, designed by the Dutch architecture firm MVRDV. Market Hall is also a combination of a market and communal living spaces. Why do we always try to learn these ideas from abroad?

We ignore the possibilities that we had and think, “How do people live above markets?” but we go abroad and say, “Wow! People live above markets!” Of course, Market Hall is a stylish building, but had we continued to think and develop these ideas we had when we weren’t very well off, we might have made something much better than before.

A store on the corner of Seosomun Apartment | Hwang Doojin

For some reason, this building is popular among scholars who study apartments. Seosomun Apartment. Personally, I like this building as well because I believe that there is a lot to learn from the way the stores on the lower floors were built. If you look at this picture, the stores are all located along the road. And it turns the corner and is connected to the shops in the next building. And this is how it’s designed not only on this side but on the main road side as well.

From the way the building corners were constructed, the designer made their thoughts on buildings and roads clear. Originally, I think it was designed to have glass walls all along Tongil-ro so that people can see inside and outside. They’re all covered now for privacy reasons, I suppose. But I highly regard its attitude toward the road.

And there is an alley behind the center of the building, and the road that is connected to the alley goes through the first floor of the apartment building. And it leads to another alley flanked by shops and stores on the other side. Although it’s old now, this one also used by to occupied by celebrities. It was like the Tower Palace of the day. It’s an old apartment building but I believe it has the basic virtue of urban architecture. This apartment has a great attitude toward a city.

Seosomun Apartment | Hwang Doojin

But this apartment was actually built on a waterway. Most of this waterway has been covered. So you can’t see it, and you only see the traces of the road that passes over the waterway. Seosomun Apartment was built on the covered road, and this waterway passes through Seosomun Park, behind Seoul Station, past Samgakji, and under Wonhyo Bridge.

That waterway is Manchocheon Stream. The place that the creature from Bong Joon-ho’s The Host lives is Manchocheon Stream. It flows down below Wonhyo Bridge. And the Gyeongui-Jungang Line of Seoul’s metro system is laid along the stream, and the soft curve of Seosomun Apartment meets with the curve of the Gyeongui-Jungang Line.

More accurately speaking Seosomun Apartment doesn’t have a curve. It is actually made up of a straight line that has been bent twice. Strangely, although it’s only been bent twice, it feels like a curve. What kind of apartments these days look like this today? Since there are a lot of good restaurants in this area, I recommend visiting it and grabbing a meal.

Rainbow cakes are the missing link

We’ve looked at residential-commercial apartments and housing in this talk. I believe that Korea hasn’t yet come up with proper urban housing. I believe that what we need in order to apply and develop the rainbow cake architecture that is suitable for cities is this commercial-residential building system, which is like the missing link in the process of the evolution of Korean architecture.

As you probably know, the reason a practicing architect like me is putting in the time and effort to visit these buildings, collect materials, write books, and give talks is because I’d like to bring attention to how to return the downtown area to the way it was during the Joseon dynasty. Had we studied the kind of architectural styles we had in Korea and continued to develop it, urban residences and landscape would’ve changed greatly.

This can’t be changed by one person—the whole city has to change. And I think the best solution is the rainbow cake architecture. Perhaps we should look at how such diverse commercial-residential apartments were built between the late 1960s and early 1970s and look for a new starting point from there.

As I’d said earlier, most of the apartments that you’ve seen today were built by unknown architects. So I dedicated my book to them. Thank you very much for listening to my long talk.

Q&A

Q. Whether it’s because of technical limitations or limitations in design, the commercial-residential complexes built in the 1960s and 1970s left a bad impression on their its residents and made people think that commercial-residential complexes aren’t great to live in. Could you explain what was so not great about them?

A. I saw these commercial-residential apartments in a more positive view because I wanted to bring attention to them and create a more positive opinion about them. But I wrote about what you just asked in my book. There were mainly two issues

At first, I was fascinated by it. A friend of mine said they lived in Pieoseon Apartment when they were young. Their father said, “Finally a nice urban commercial-residential complex has been built in Seoul, in Korea, like in other big cities around the world. So we should go live there.” So their whole family moved into the apartment. Since it was an advanced building, celebrities and high ranking officials lived there.

But then they realized that there were problems, like noises, smells, and things like that from the stores and shops below. And the danger of fire. I think these were the two big things. The discomfort of living in a same building as stores and shops, and fire. And when you search old newspapers with the keywords commercial-residential apartments and fire, you’ll see a number of the apartments mentioned in this book. Buildings that didn’t pass fire inspection, etc.

The way I interpret that is, Korea’s architectural design technology at the time was not up to the level of designing commercial-residential apartments to create a pleasant environment. Particularly in terms of fire safety. I believe that now we have that technology in the Korean architecture community. So it’s a problem that can be resolved with a more developed design. In that aspect, I think commercial-residential complexes were created several decades too early for us. It would’ve been great if they became the main type of buildings at the time.

And as I mentioned earlier, it was “accidental modernism”. Our technology wasn’t enough to support it, but the architectural style came to us. That’s one point of regret, but I believe that’s not reason enough to permanently exclude commercial-residential apartments from the past from our lives. And that’s why I wrote this book.

Q. I can see that you really have a lot of affection for the buildings. If you were to choose a favorite, which would it be?

A. That’s a question I’ve waited for someone to ask. I think it’s a great last question. In terms of architectural experiment, my favorite one is Daeshin Apartment. It’s Y-shaped. That was really impressive and shocking to me. And I like if for a number of personal reasons. I have a lot of reasons to be in that area; I know someone who lives there; we’ve gone there for a visit during today’s excursion; I saw a film there when I was young; I still go eat at the naengmyeon restaurant there…

For similar reasons, I also like Nagwon Sangga. These are the two of my favorites. And Seosomun Apartment, which makes me want to stop by and take a look for some reason whenever I’m in the area.