What finally pushed me out to the Candlelight Protests in Seoul was Donald Trump’s presidential victory. The two have nothing in common yet are viscerally tied to my identity as a Korean American. I’m a third culture kid and a 1.5 generation immigrant. I left Korea at eight to live in Indonesia, then moved to the USA as a temporary and later permanent resident. It is now just short of 10 years since I gained my US citizenship. Most of my life has been spent in the States but I was never able to accept it as my home country, and I figured the feeling was mutual.

But back to Seoul. It was the third Saturday protest since the news broke on the incriminating evidence on the illegitimate presidential adviser. The daily news was impossible to keep up with, but there was a clear sinking realization that there had been nobody steering this ship over the past few years as the president whitewashed history, conglomerates bribed their way to wealth, youth unemployment rates rose, and hundreds died in the Sewol Ferry disaster as we helplessly looked on. The demand for justice on these and other issues culminated in the call for the president’s resignation.

Civil society organizations and individual citizens with their home-made flags and placards poured out to the streets with their toddlers on their shoulders. Teenagers in school uniforms, young lovers, middle-aged men and elderly ladies chattered happily with their fellow protesters on a calm and festive afternoon. I marched joining them off and on in the four-four chant led by the megaphone call—Park/Geun/hye/neun—and response—ha/ya/ha/ra.[1] Protesters with their songs and ruckus pungmulnori (traditional percussion troop performance) streamed in from side streets to City Hall and Gwanghwamun for the packed evening. Vendors sold hot snacks and candles for a few thousand won. Pop stars performed, singing protest songs remixed to the tune of Feliz Navidad. Kids played tag and the riot police idly looked on.

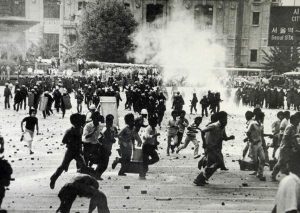

Seoul protest, 1980s.

The remarkable lack of tension might look half-hearted compared to the days of Molotov cocktails. But the protests in South Korea have been frequent and deadly throughout its military dictatorship and democratization, and with the recent death of a farmer/activist caused by police water cannon, the citizens seem to have collectively wised up. So level-headed were they that many even brought their own trash bags to quietly pick up after others as a show of social responsibility. The unhurried march seemed a sign of clear-eyed humility—a willingness to lend one more warm body and voice to the sea of people, fully aware of the long fight ahead.

Considering the historical failures of the legal and social institutions to bring the rich and the powerful to account, there is no guaranteeing the results for this round. But something is indeed different this time. There is a nation-wide resolve to ensure the laws function as they should, and that elected officials uphold a constitution that declares that the sovereignty of the democratic republic resides in, and emanates from, the people. We, the people, are sovereign.

Korean Constitution — Article 1: Democracy

(1) The Republic of Korea shall be a democratic republic.

(2) The sovereignty of the Republic of Korea shall reside in the people, and all state authority shall emanate from the people.

Source: National Assembly

Song: 대한민국은 민주공화국이다

I say we. But am I included in the collective? In a previous march, about the Sewol Ferry disaster, my voice faltered and I kept the placard low at elbow height. It was as if I were undercover pretending to be someone I wasn’t. While others are secure in their right to demand justice based on their status as Korean citizens—the gukmin—I forfeited my own Korean citizenship when I was naturalized. I am constantly pushing back mild paranoia that someone might see through me, point an accusing finger and say, “You traitor. You have no right to protest. Yankee go home”. And legally they might be right. What does it mean to be a citizen, in both the legal and the metaphorical sense? Have I forfeited my right to protest against injustice in Korea?

On the other side of the Pacific a president was determined in an election in which I had neglected my right to vote. I have been a tax-paying resident and citizen but have yet to cast a vote in any election. As it became clear that Donald J. Trump would be the next president of the United States, the utter guilt for taking my right for granted, and for having contributed to Trump’s victory made me sick to my stomach. In my past few years living in Korea I have seen its citizens call this place hell. If such anger and shame for one’s country is a mark of a citizen, then I finally became a US citizen the day Trump got elected. Finally I started caring enough to lament.

I took that same lament into the march in Seoul that Saturday. Call it an act of penance; it was more unbearable to stay away.

Citizenship is such a big and abstract concept. Korea is no longer my country of citizenship, but it is my place of birth and current home. The United States is where I learned the liberal democratic ideals. I am still figuring out how to love them both, without giving up on my motherland or detaching from the homeland that now seems set on rejecting my non-white identity. As one both uprooted and en route, it is difficult to commit to an idea of nation at all. But I am convinced that the small actions I take for justice and compassion wherever I am do reach beyond national borders and across the globe.

More at The Dissolve

- The Great Crevasse that Cuts Through the Squares

- Ode to MBC

- Waxing lyrical on K-pop: An in-depth interview with writer Kim Eana

- Tiger moms and Korean moms—is there a difference? Part 1 of a conversation on Korean parenting.

- Exploring “El Mapa de la Vida”, with the author and illustrator Oh YoungWook