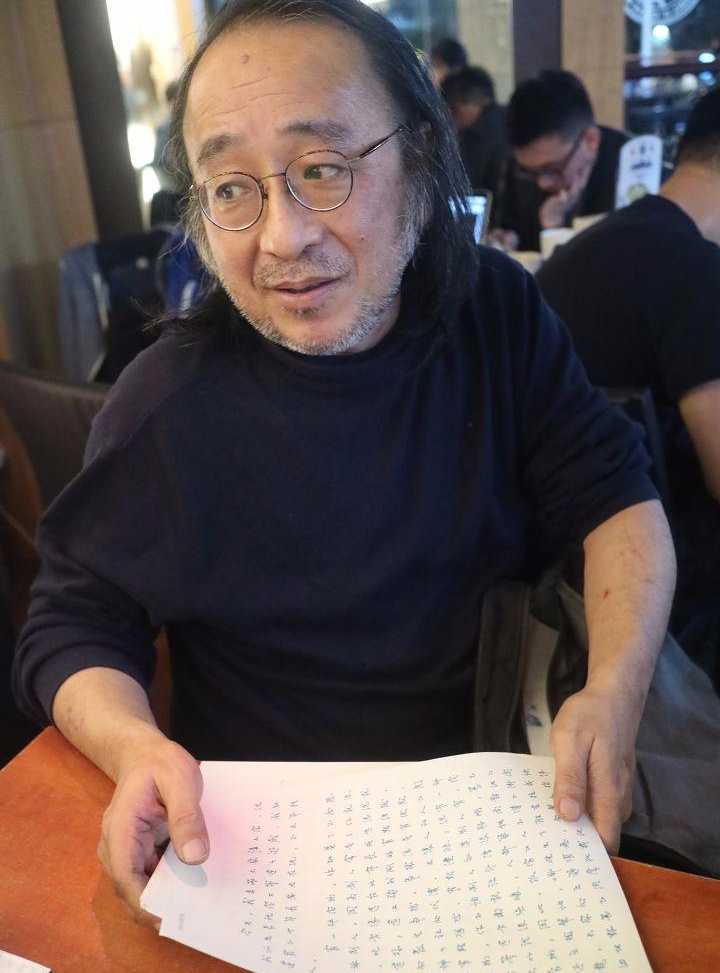

Today, I present an interview with Tang Nuo, a Taiwanese writer and the author of The Story of Reading.

Positioning himself as reader rather than writer, Tang Nuo takes Gabriel García Márquez’s The General in His Labyrinth as a foundation to answer every possible question on the art of reading.

This approach makes for a phenomenological contemplation on the very essence of reading. The range and depth of his thoughts make the book stand head and shoulders above others of the genre. Tang Nuo is, for this books journalist, a messenger sent by the god of reading.

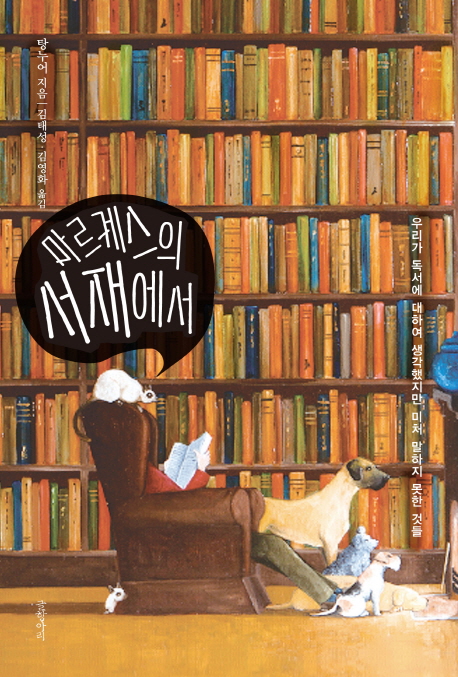

The Story of Reading was released in Taiwan in 2007. A Korean translation didn’t appear until February 2017 (under the title 마르케스의 서재에서, meaning ‘At Márquez’s Study’) and it seems there are no plans for an English version, unfortunately.

I interviewed him in person in Taipei and by email afterwards. The translator of the Korean book, Kim Tae-song, kindly assisted.

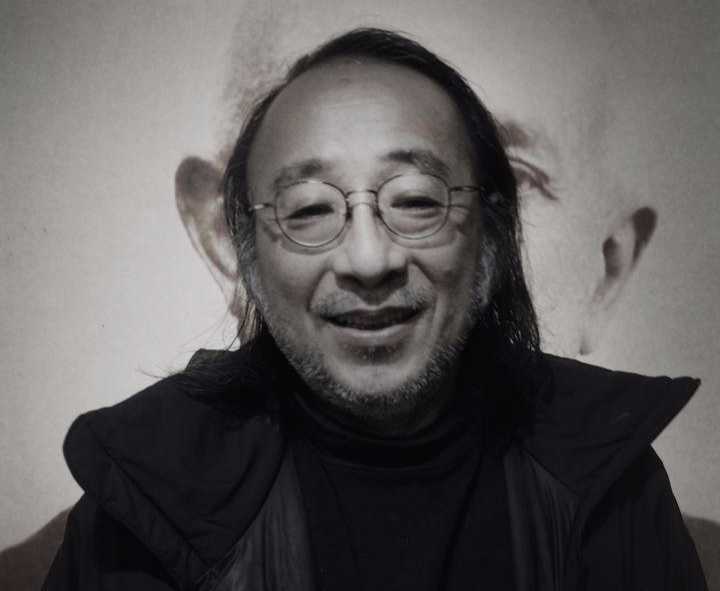

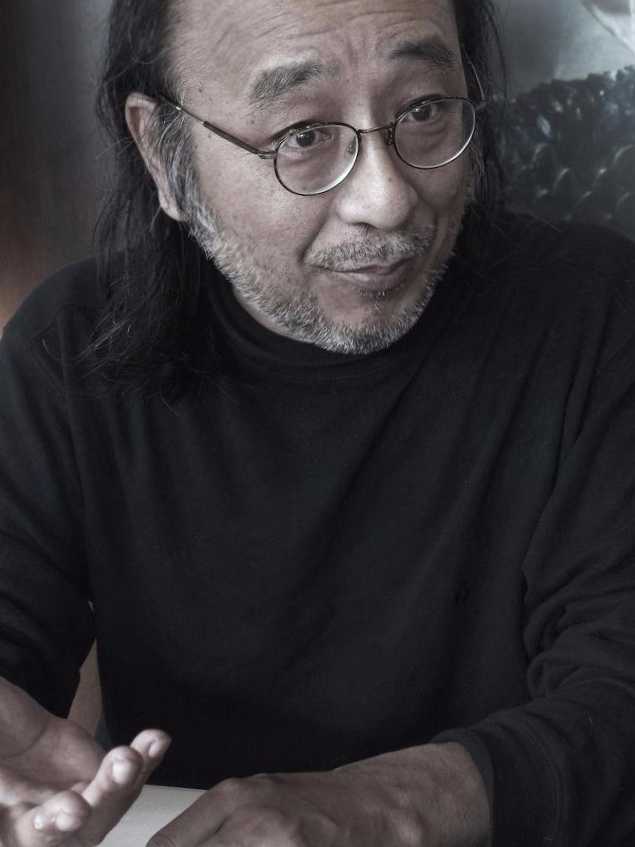

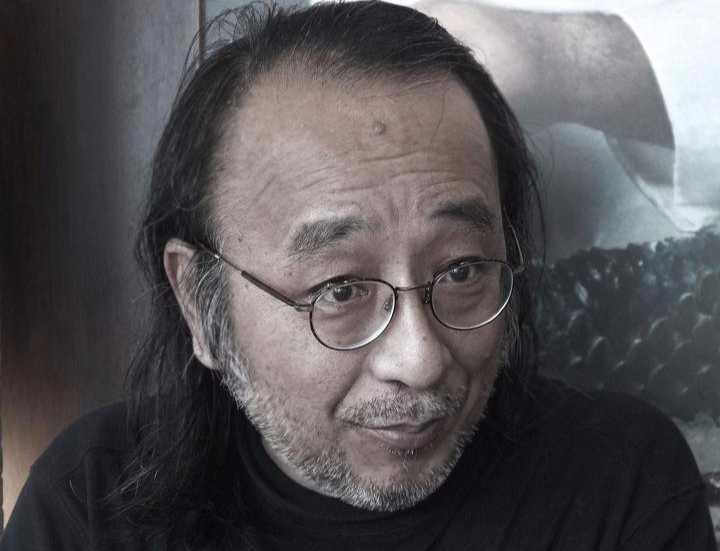

Tang Nuo

Born Xie Caijun (謝材俊) in Taiwan in 1956, Tang Nuo graduated from National Taiwan University with a degree in history. Since then, he has been a self-proclaimed ‘professional reader’ focused on both reading and writing about reading. He is married to Chu T’ien-hsin, a writer known as the Taiwainese Françoise Sagan. Chu studied history at the same university and is the daughter of the anti-Communist writer Chu Hsi-ning.

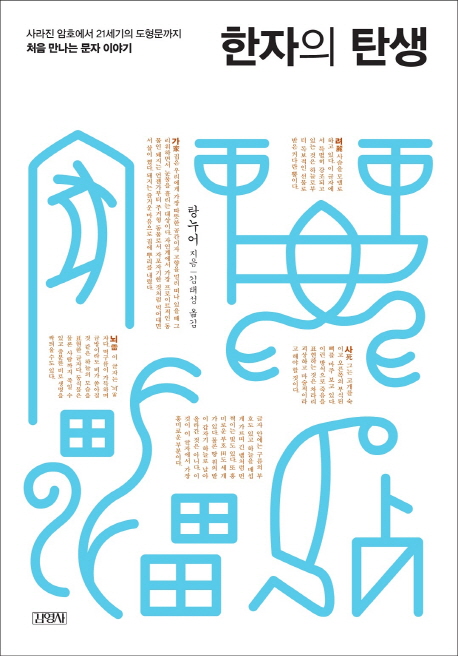

Tang’s works include The Story of Reading and The Story of Chinese Characters, both of which have been translated into Korean, as well as Time of Readers, At the End, and Commentary of Zuo.

The Story of Reading

I’ve used many different pen names. When I was working in the publishing industry, I edited detective novels and one point even used the name of an Agatha Christie detective. Tang Nuo is the closest Chinese transliteration of the name Donald. ‘Donald Duck’ feels nothing like me: funny but not hard working. But that’s where I got my pen name.

My wife and friends tell me I should use my real name instead of a pen name, but I believe that using one helps me to maintain a distance between myself and my writing and to better express the person that I am.

I set foot in the publishing industry at a relatively early age. In college, I started writing books and edited magazines. But I thought of my work then as a kind of training. So I don’t think I can say that I was fully engaged in the publishing industry back then.

What I think of as my own writings came later in life, after 1992. I consider The Story of Chinese Characters (文字的故事) to be my first book, and The Story of Reading (閱讀的故事) my second.

There’s a reason why I titled them “The Story of…”. When I first entered the publishing industry, I thought of doing a series, like “The Story of Humanity”, “The Story of Religion”, or “The Story of Jesus”. Those “stories” seemed trendy in publishing industries around the world at the time.

The idea was to explain concepts that we encounter frequently but are not well informed about. I thought of “stories” as explanations about a topic. A story doesn’t have to be deep. Broad and universal is better—enough to paint a clear picture of the topic.

I thought it would be great to discuss a number of topics, like the Constitution, nation, and authority, in a story-like narrative. So I talked with the film director Hou Hsiao-hsien [侯孝賢, Director of The Assassin], a personal friend; the novelist Chu T’ien-hsin, my wife; and renowned Taiwanese lawmakers. And I told them, “You should write about film”, “You should write about fiction”, “You should write about the nation”.

When I first mentioned the project, they were all interested. But we were all busy with work and after three years I realized that I was the only one who had actually gone through with the plan. That’s how The Story of Chinese Characters and The Story of Reading were born.

The Story of Chinese Characters was a relatively simple book. It contains the material from 13 television episodes that I’d written, back when I was serving as an advisor for a broadcasting company along with Director Hou Hsiao-hsien and another writer. Since it was intended for television, the content was relatively simple.

In contrast, there were no constraints on this book—The Story of Reading—so I poured all my thoughts into it. That’s why it turned out a bit heavy.

I wrote it from the perspective of a reader. It may be that some of the book’s readers come at it as writers. But from my end, at least, this book contains thoughts and experiences from the position of a reader.

It’s already been a long time since I wrote it (ten years), and I get embarrassed when I re-read it. But I can say that I gave each and every word careful consideration.

The reaction from the readers and the market wasn’t bad. The book was also published in mainland China and Hong Kong, and it was received well there as well. In Hong Kong, my book was featured in Yazhou Zhoukan, an international affairs journal. I heard that Korean readers also liked my book. It’s probably because the translators did a good job. (laughter)

When The Story of Reading was first published in Taiwan, I did have a large group of guaranteed readers, just enough so that the publisher didn’t make a loss.

The reception for The Story of Chinese Characters was different in Taiwan and in China. It sold very well in Taiwan—four times more than The Story of Reading. But it didn’t do very well in China. I think that maybe Chinese readers didn’t appreciate a Taiwanese writer from the periphery, far from the mainland, analyzing Chinese characters.

A unique approach

Method is important in writing.

I chose this approach after contemplating what structure and writing method would get across what I need to say as accurately as possible. It’s easy to forget about the temperature or the feelings and the details of a story when you’re simply telling facts. So I thought about it a lot and settled on this format.

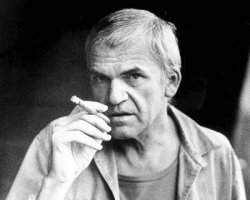

I used Márquez’s The General in His Labyrinth as a guide because I needed a view, “somewhere far away”. I thought that this view would help me create a conversation and draw out my thoughts. I found a way to proceed by responding to and conversing with the paragraphs from the novel.

Márquez is my favorite novelist, and a very humble writer. But I only picked The General in His Labyrinth as a guide by chance. I could have done the same thing with Borges or Chekov.

I don’t believe that there is a difference. Whether the author is from the West or the East—his nationality isn’t important. I’ve also written a book on the Chinese classic Commentary of Zuo. When I do an in-depth reading of a book, I think I become an anarchist. [In the book, he uses the expression “citizen of the Republic of Literary People”, free of any nation state or country.]

There is more than a little danger in emphasizing only the pleasure of reading, as people often do—especially so when someone’s about to start reading, and they only expect pleasure and excitement from reading.

In fact, reading a book can be rather tiring and dull at times. A lot of the time, it also requires a certain amount of coercion. So when people try to convince others to read simply for pleasure, new readers might get disappointed and end up throwing the book away.

If you’re only looking for pleasure, it would be much more fun and exciting to play computer games, watch television on the sofa, chat with people or criticize people online, or go to a karaoke room.

But there are many good things in the world that cannot be described as pleasurable or as a form of play. And reading is one of them.

‘Agitation’ is inevitable

Fundamentally, reading looks toward the distance that Milan Kundera described. When you read, you look up and into the big world, toward something you don’t know yet, you’ve never seen, thought of, or ever had.

The agitation you experience in the process is inevitable. It is a state of psychological contemplation that is difficult to endure, but generally, it does not get worse than that. It doesn’t bring worse pain or danger. Therefore the state of agitation is not difficult to endure.

Rather, great readers welcome such agitation. Although they do feel uncomfortable since something has not been resolved, they realize that something is just up ahead, not too far in the distance. It’s similar to ships realizing that they must not be too far from land when they find trash floating on the ocean surface. So agitation is also a very reliable sign.

This kind of agitation can be resolved depending on the progress of reading, but at times it becomes even more specific and clear, like fragments coming together. Or it can represent something completely new. Readers can feel that at least they are approaching the right question. That’s why countless great writers say that finding the right question is even more important than the right answer.

Good questions spark contemplation. They allow people to live with the world, and they allow people and the world to form a friendly, conversational relationship, ruminating and keeping each other company. On the other hand, quick answers tend to destroy problems and close the door to contemplation. It’s like a painkiller that helps you get a deep sleep.

Through reading, we arrive in a higher dimension. We get to see the same problems that the great writers have already seen and ask the same questions. We become part of the conversation. In this process, the feeling of agitation subsides and dissolves into extremely elaborate and detailed forms. And we realize that we’ve become better persons than we were before.

But the power of contemplation to find questions is forever stronger than its power to find answers. As a result, contemplation brings us credible answers, but it also brings us ten, twenty new questions.

That’s why agitation, in relation to reading, does not disappear. It’s like the ebb and flow of tides. Until our brains stop working and our sensory organs close up altogether, agitation will be part of reading. That’s why Borges said he could only write about his own agitation and that the history of human contemplation is a history of a series of agitations.

The fundamental deficiency of books

I think reading begins from a type of good-natured thinking. For instance, wanting to understand the world and people, wanting to sympathize with others, or wanting to become a better person.

I believe that everyone, at certain points in his or her life (particularly in youth when hearts are more generous) reads books, gains insight, and learns certain ideas. But these flames of good-natured thought can easily be extinguished by neglect.

The difficulty of reading lies not with starting to read but in continuing to read. The real reason that the flames of reading flicker out stems from how people prioritize.

People who believe that a beautiful figure is important will watch what they eat, go running, and work out every day. They even get plastic surgery. I think that those activities are much harder, more dangerous, and cost much more money than reading a book, but there are a lot of people who prioritize that way.

In the end, it depends on what you really want to do and what kind of person you want to be. The reason people read books despite the evident agitation is because there is pleasure that is worth overcoming the difficulties.

Then what is that pleasure? I wrote about it in my book, quoting a Japanese go player. When people asked Ogaka Tomoko about the pleasure of go games, she said, “It’s fun, but not the same ‘fun’ that people talk about when they say they ‘have fun’.”

I would also answer that I do find reading pleasurable, but not in the way you might first think. The pleasure I gain from reading a book is a ‘weighty’ pleasure. It’s different from excitement or joy. It’s also a different kind of fun than the fun I have when I watch television dramas.

Books are paths through which we arrive at knowledge that writers have accumulated over decades, and for a low price compared to the value. And it’s a pity that people spend freely for other things but become stingy when it comes to buying books.

I have no interest in convincing people of my view of life. It’s just that I like feeling that my life is substantively, realistically, and firmly grounded—rooted in the ground—and through this, I feel that my life is genuine and that I haven’t wasted it.

I don’t believe that I, or anyone else, could change the whole world. I also believe that the differences between individuals and groups, whether small or great, are among the best things that the world allows us.

I assume that most individuals could, if they wanted, find small, friendly spaces to read in whenever they want.

Failed books are worth reading

Fundamentally I believe they are equal. Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America that the spread of equality cannot be stopped, and I agree. But it is true that rankings are created in all areas.

It’s the same as Einstein being more correct than 200 million people in physics. In that aspect, it is possible that there are different levels in reading. Obviously there has to be a difference between someone who has been reading for 30 years and someone who just started reading.

Generally when reading, I would say that it would be reasonable to start with the “classics”. History has proven them to be great. But reading a book that was not a success is like taking one step further in reading. It’s a more elaborate, dense, and traditional way of reading. This kind of reading is necessary, especially for people who write.

‘Failure’ has many facets and meanings. The failed works of great writers in particular, such as Tolstoy’s Resurrection, Gogol’s Dead Souls or James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake, cannot be simply pegged as failures.

It’s because sometimes writers take on difficult challenges, and these works might have been their failed attempts at something that is nearly impossible. These failures are remarkably precious, grand and beautiful, and sufficiently experienced readers can sense wonders in these works.

They can experience new things with these writers or the attempt to reach the peak of human contemplation and imagination. Also, while reading unsuccessful works, readers can try and polish the sentences themselves, realize that their own attempts are unnatural, and learn new things.

To take an example, I’m sure there’s a “good restaurant” craze in South Korea. So the answer to your question would be evident when you compare online encyclopedias that contain extensive digital information about restaurants, and books by certain writers that focus on a few select restaurants.

Reading and writing are not mechanical storage and recall; they lie somewhere between memories and oblivion.

And you are making a choice. Reading a book means you’re making a choice. And books contain interpretations, and sometimes spark interaction. People can become more perplexed when they come face to face with storage, masses of knowledge. In Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, the ark of the covenant is hidden somewhere, but people can’t find it because there are so many of the same boxes. That’s the weakness of encyclopedias, and of digital memory.

In a society where reading has been democratized, there will be an equality of knowledge. But the democratization of reading is just democratization. If enhancement of a society is to occur, I believe that the elites of the society should read more and support reading and lead the society in that direction.

I heard that Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century sold five million copies across the world. But even if only five hundred copies were sold, its value would be unchanged because it altered the course of the discussion on how society should operate.

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty

It actually began sort of as a joke. These days, when I read a book, I think about the age of the author when he or she wrote the book. And I realized that many of the great books were written by authors at much younger ages than mine.

The Chinese novelist Eileen Chang (張愛玲, 1920-1950) wrote all her great works before the age of 40. Karl Marx wrote the Communist Manifesto at the age of 30, and Engels was 28. Walter Benjamin committed suicide before the age of 40.

Reading those works at my age, I thought about how these writers started writing at such a young age, and that enabled me to have more detailed conversation with the books.

Every time I read the same book again and again, I find new things that I haven’t noticed before. Depending on when I read, and what kind of experiences I had, it feels different.

I don’t even know how many times I reread Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. My wife Chu T’ien-hsin has read it so many times that she can recite it. I believe all books are worth reading. Except for my books or books that are out of print, I reread all books.

On the other hand, I feel a sense of frustration when I see people make the same mistakes, even though they were written down in books a hundred or two hundred years ago.

Taiwan and South Korea

In any society, there is a period of futility. Humanity has doubted knowledge for the past 200 years. After my book At the End was published, I was invited by Peking University in China to give a lecture under the theme of “To believe or not to believe”.

There I talked about how humanity has believed so easily in things such as religion, family, and love, and for so long. I said that people around the world started to become skeptical of the values that humans have created and gotten used to.

Our productivity improved dramatically, but there are questions about whether the quality of individual lives has improved by the same extent. So I talked about how the whole world is questioning the achievements of humanity, and I discussed that in terms of Taiwan.

The lecture at Peking University wasn’t received well at the time. I think it was because the topic was too advanced for the Chinese system. Also, since China is full of self-confidence, it may be that themes like skepticism and futility are difficult to accept there.

It’s the same in Taiwan. Medicine is the biggest achievement of this era. And it’s an industry that is bound to grow. In the past, the general idea was that people were fundamentally healthy. Now, we say that the thing that people lack the most is health.

In the past, we had normal thoughts and emotions, and we expressed joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure in a normal way. There were doubts that were bound to exist and questions that needed to be solved. Now, diseases fall into that category. Since there are illnesses, we obviously need medicine.

Of course, most health supplements and foods are basically ‘harmless’. (There are so many stores that sell such things and their numbers are growing). They’re just corn starch with vitamins added.

And they are quickly flushed out of our system. People tend to find consolation in the fact that they are cared for and understood by others, and that others just like themselves have problems in their lives.

This isn’t a troublesome phenomenon, and it is completely unrelated to the reading we’ve been talking about. I sometimes wonder about selling the books I like in pharmacies and health supplement stores. Maybe that will happen in the future.

But a true reader won’t fall into self-pity. She won’t be frequently looking at herself in the mirror. Because the world is too big. And on a more serious note, true readers are much more interested in others than themselves.

The reason is simple. The history of humanity has an eternally bigger sorrow and a deeper and heavier fate. Even in a normal state, the world has more injustice and unfairness than the always flowing and undulating stream of love and hatred. In this world, how could we only talk about the trivial “forgettable” (in the sense used by Milan Kundera) things about ourselves?

Tocqueville already predicted something like this, 200 years ago. In his godlike achievement titled Democracy in America, he pointed out several times that the principle of universal equality was a big flow that could not be stopped.

The equality of humans is a very noble and great cause. But inevitably, there will be historical repercussions. This tide of history can threaten or annihilate some things. We might lose those elaborate and deep values, like liberty, singularity, and others that can only be delivered upward in a vertical hierarchy.

Tocqueville believed that equality was more important than liberty. He had bigger expectations for humanity. In the era of the great revolution, when people were listing liberty, equality, and fraternity as though they were all the same type of products, he wisely saw through the fact that liberty and equality will betray and interfere with each other in the future.

In the end, the composition and the legacy of humanity’s achievements of contemplation is going to take the shape of a pyramid. It’s going to be unequal. The absolute equality of the common denominator of the collective is going to be at the very bottom of the pyramid. When this pyramid becomes the ultimate standard for judgment, rooted in people’s hearts, it will bring us the ordinary, mediocrity (languid comfort), and oblivion.

We will quickly start to forget things one by one and give up. How great it was for humans (as individuals) in the early days! Borges described this downwards process as the gravitation of the tiring history of humanity. He’s referring to the flattening of the world and the pulling down to earth of all that flies. Milan Kundera was correct. Humans no longer have things “in the distance”.

Habits

Usually I leave home at nine in the morning and go to a coffee shop. Because I love reading so much, I end up only reading instead of writing when I’m home. So I write in coffee shops. I can concentrate on writing there.

Another reason I go to coffee shops is because it’s easy to get lax if I stay home all day, and it makes me feel isolated from the world. Getting out of the house and walking outside makes me feel like I’m maintaining a relationship with the rest of the world.

There’s a café on Yongkang Street in the city that I used to frequent, but it recently closed down, so I feel a bit distressed. In the past, I used to walk back and forth between home and that coffee shop and watch the number of Korean and mainland Chinese tourists grow.

I read in the afternoons and go out in the evening to check on stray cats. I walk for about an hour and a half—nine or ten kilometers.

We all like to walk. We mainly walk around when we’re in Kyoto too. Traveling by car feels too fast. For the same reason, we don’t really use smartphones or computers.

Every Wednesday, I go to work at a broadcasting company. I’m a consultant, which gives me fixed income, financially. I’m a consultant for a program titled “Wednesday”. So I don’t make plans on Wednesday afternoons.

I travel abroad about once a year. I rarely go to China unless something special comes up. I go to China or Korea if I have to, but in any other cases, I refuse the invitations. I tend to refuse all interviews in Taiwan as well.

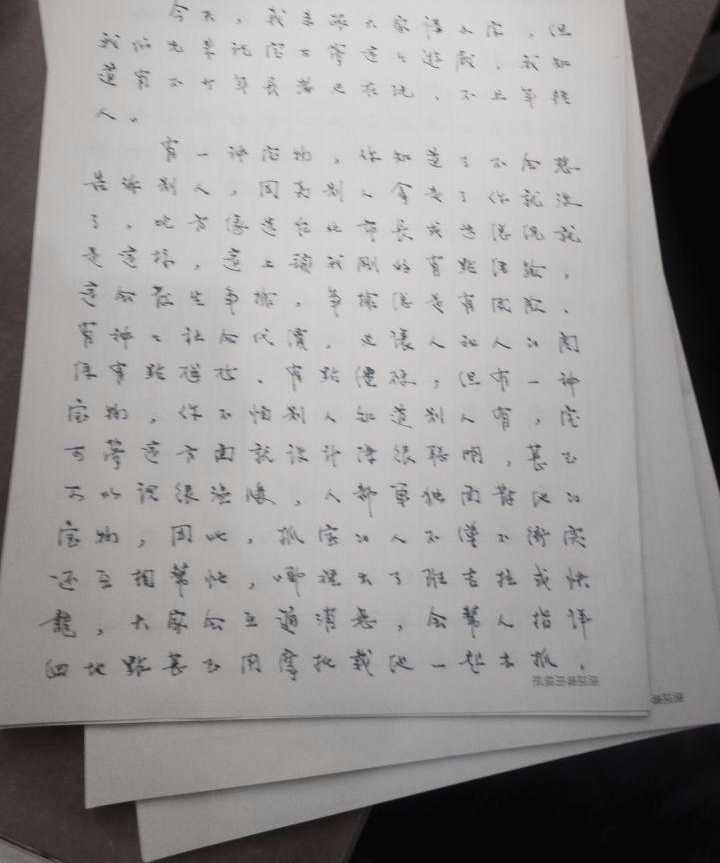

I do have an old computer at home. I only use the internet when I have to look for information I need. When I write, I use a fountain pen and paper. I carry several pens around. And I write on the paper that my publisher made for me. Usually I write about 7,000 characters a day.

Intellectual journeys

I majored in history in university. My father was an architecture professor. Everyone wanted me to follow in my father’s footsteps. I did quite well in physics and mathematics when I was in high school. But I never thought of studying anything other than liberal arts.

I enrolled in National Taiwan University and studied with my wife Chu T’ien-hsin under Professor Heo Nan-cheong. He told us to study the basics in physics, economics, and political science, so that’s how I studied throughout all my years in university.

For over ten years from my junior year in university until my wife gave birth, I studied between eight to ten hours every day. That’s when I realized that it takes me about half a year to a year to learn about something that I’ve not studied before. Until then, I spent days reading but not understanding. Looking back, that happened quite a few times.

The book that I’m writing now has parts on the economy, and it was difficult to write about it. In the past, I was able to read and understand economics, but I had trouble writing about it. But I came to understand it after about half a year to a year of studying it. I’m still interested in learning about different fields.

The title of the thick book At the End I mentioned earlier is about my thoughts and reports on the realities of my generation, and it deals with a variety of topics. Since the book analyzes Taiwan in the present era, I had to study many different areas in order to get a proper grip on the realities of our society.

I hope you don’t misjudge me for studying various areas. It’s not because of my vanity, but because of curiosity. Studying isn’t something you do to look good, but because it’s necessary.

If you like something before the age of 20, I think you can say you do it blindly. Compared to my family or friends, I did like books more and read a lot. It’s difficult to tell whether it was because of my personality, or whether I came to this point due to some kind of fate or opportunity.

Taiwan was very poor before 1968. Everyone was poor at the time, but people had a lot of children. So everyone had to be raised by the will of heaven. There weren’t many books, and they were precious.

It felt as though all books emitted light and contained some kind of mysterious world. Whenever I opened a book, I felt a jolt of excitement run through me. It was indescribable. That’s what I remember the most.

At the age of 20, I founded a literary magazine called Sansan Jikan (三三集刊) with a few of my friends. As I worked on the publication, I realized how ignorant and weak I was. That was the beginning of true reading for me. Since then, I’ve been reading six to eight hours every day.

After the age of 20, there were times where I had to read out of responsibility. For instance, fields like economics, physics, and mathematics were areas that I only had a basic knowledge of, so it was necessary. There was much I didn’t know so I had to read and figure things out.

I believe that if we don’t fill these gaps properly, our opinions about the world will not be whole, which can result in biases, making us see things wrongly and talk about them wrongly.

Simply put, I’m trying to accurately understand the world and the times I live in, and just like Hannah Arendt, who understood the perspectives of different generations, I’m trying to leave the words that are necessary. I believe this is the duty of a writer.

Working through doubt

I’m sure I have. When I look back on it, the biggest crisis I encountered was when I started reading about economics, physics, and mathematics. These professional academic fields have their own languages and ways of thinking. On top of that, so much knowledge has accumulated over several thousands of years, and so much development has happened that it took me over half a year to penetrate their strongholds.

No matter how much I read, I thought it was absurd. I knew all of the words, but when they were put together, I had no idea what it meant. It seemed like all the characters were like passwords, so at first I questioned my own brain. If that weren’t the case, then how was it possible for me to not understand something that so many people knew?

So I suppose the biggest crisis one encounters in reading is perhaps the lack of genuine progress. You can’t set a short-term goal. It’s like walking through a vast space without a marker. While you read, you can’t feel that you’re making progress.

On the other hand, internet games you play on your computer show people’s ability in figures. So in three days or a week, you can go up several levels. But you don’t get such frequent encouragements with reading, so you want visible goals and get easily discouraged.

My achievements in reading are not enough for other people to take as a lesson. But I think I can say this: I was able to write something that I was relatively satisfied with at the age of 45. So I see the age of 45 was the first year of my writing. The day my first real book was finished came 25 years after I truly started to read. It took a long time.

I believe the act of measuring your achievements in reading only brings you further away from the world of reading. The best way is to make a habit of reading, so that it becomes part of your life, like brushing your teeth after a meal.

It might require an element of force or self-deception. Bhaskar said, “People gamble forever with their superstitions.” It doesn’t matter how you do it, as long as you make reading a habit.

I do believe it’s possible. You will need a certain amount of training or education. This might sound inappropriate in this time and age where the emphasis is on individual personality and freedom (all the while subtly asserting futility and negligence).

The liberalist philosopher John Stuart Mill was able to grow into a great thinker thanks to his father’s ‘education’ and ‘training’. From what I know, he read more books before the age of 20 than any other person has, and he received great basic training in the history of mankind. He was a scarily great person, both quantitatively and qualitatively. He did pay for that with a mental breakdown.

The fact that something is good doesn’t mean that it is fun or that you can find a way to make it fun. In this aspect, when you look at books as achievements of human thinking and compare them to ‘play’, they seem grand, solemn, deep. This trend seems to grow stronger the further back in history you go.

Plato also said that the things that are the easiest to say come at the very end. Reading is accompanied by an element of coercion. The Chinese word for ‘coercion’ (勉強) means ‘to study hard’ in Japanese. In a way, reading means appropriately coercing oneself.

Deciding what to read

There’s no particular method. But it’s clear that reading guides the reader. It happens as the need arises. This need lets us pick out the appropriate books at the right moment. Or it could happen through appreciation. It is difficult to define or clarify exactly what appreciation is; it’s a general eye for things, an overall ability to judge and evaluate things.

Great philosopher Kant wanted to describe “appreciation” clearly in his later years. He wanted to assign a clear enough logical basis to it. But he didn’t succeed. Despite that, Kant knew and strongly believed that the highest, deepest, most elaborate, and greatest things that humans have can only be recognized through appreciation.

At one point, I also said something dramatic, to the effect of: “The book you will read next is in the book you are reading now.” Books call to other books of similar types. They breathe with each other and interpret each other. We need to be able to believe in and listen to their microscopic yet reliable voices.

Calvino said that, and Borges also said that they are happier as readers than writers. Borges said, “I can read all the best and the most beautiful books. But (as a writer) I can only write those few things that I can write.”

In the end, reading is a one-sided harvest, an injection. In the process of reading, people feel that places in their hearts become “filled”. That’s why they have things to say, and they can confirm their feelings. And going a step further, they think and discuss and look for companions. All of this leads readers to books without them even realizing it.

I sometimes think that I can only take and not give. Isn’t this too selfish? We could say that the achievements of human contemplation and writing are a huge pond (I’d once said that they were a sea, but gradually narrowed it down to a pond. It would be correct to say that the world we live in is constantly becoming smaller.) There, we can temporarily take what we need.

All writing is the same. Writers are and must be, first and foremost, readers. As a result, writing is indeed “repayment”. Several years after you finish writing and you become poor, you can still go on earning as a reader. In terms of the quality and quantity of our earnings and repayments, we will forever be on the advantageous side. It’s nearly free.

Being married to the “best writer in Taiwan”

I hear that your wife, Chu T’ien-hsin, is regarded as Taiwan’s best writer. Does that make your life difficult at all?

[Chu T’ien-hsin is known as the Taiwanese Françoise Sagan. Tang Nuo is known as a devoted husband. I asked this question to tease him, because he said he goes to a café with his wife every day to read, but his answer was touching.]

My difficulties usually rise from other people’s good will. People often seem to pity my daily living. And they think of all kinds of difficulties that I might encounter, as though I chose marriage because I was unwise, as though I’ve gone to purgatory.

But that’s not true. I really like my wife, Chu T’ien-hsin. I first met her 40 years ago and married her 30 years ago. For 30 years, we haven’t hid anything from each other. We read together, talk together, and together protest against things that need to be protested against.

And I still like her as much as before. To be exact, even if my friends think that my wife is strict and that her standards are growing stricter and stricter, she is a person worth loving.

She didn’t need to be this great to be my wife. And being my wife might not be as important to her as it is to me. But what is really important is that she is a great writer.

She is very caring, sensitive, righteous, and remembers even the most trivial things, and these qualities often get her into trouble. So I do my best not to become a distraction to her.

Occasionally, there are times when I can’t even dare console her. It’s because of her unique difficulties in life. That is probably what’s at the heart of her writing. And I don’t have the courage to risk destroying that.

Kyoto is my second favorite city. My all time favorite city is London—except for the food. But London is too far and too expensive. It’s far more than I can handle.

Over the years, Kyoto has become another home for us. Sometimes going to Kyoto feels like “returning to my old hometown”. We go once every year or two and I can tell the small differences, traces of time that are barely visible like spider webs, such as certain streets, stores in certain corners, people’s facial expressions, attire, behavior, etc.

We tend to take for granted the places that remain miraculously unchanged. I see Kyoto as a existing a priori. And it gives me a bit of courage. The courage to believe in beautiful things, the courage to explain, advocate, and argue for the sake of beautiful things. I feel that this courage is constantly being washed away in our lives.

I’m sorry, but I don’t speak Korean, so I can only read books that have been translated into Chinese. On top of that, translation of Korean literature hasn’t taken off yet in Taiwan. So I don’t have enough understanding of Korean literature and books to make any comment.

How to grow old

I recently read How to Grow Old, written by a friend from my youth named Chang Qing.

She is a medical doctor and a fiction writer, and she just quit her job at an international pharmaceutical company with a one million yuan salary [150,000 USD]. It felt like she was moving backward in the world.

Chang Qing’s book has a “body”. Her writing is based on the firm ground of reliable and agile medical training and experience. And she is astonishingly knowledgable on the liberal arts, and she reads books from all around the world. This kind of preparation for writing is very rare.

But in the short term, her background is a handicap. Her style of writing takes longer to move and awaken readers. And her writing transcends the needs of the common denominator. Her book would be too big of a challenge for the nature and the level of many readers.

Simultaneously, her attitude can make her come across as over-rational and perfectionistic. Plus, her writing is very discreet. Again, this kind of writing takes time to bloom. Just like all the writers who overcame all kinds of doubts and attacks over a long period of time.

It reminds me that writing requires the will of your entire life. It’s not something that passes quickly like a firework in your youth. I’m reading her book with serious determination.

Tang’s next book

Since The Story of Reading was published, some readers complain that I’m not writing about NBA games or detective novels. But I am constantly thinking through the issue of reading. I believe I like and know what it is to be a reader, and I will probably continue to write as one.

I am working on a new book right now. It’s about age, reading, and writing. I will soon be in my 60s, and that’s an age that signals the beginning of old age, an age that brings you closer to death.

So I’m writing about the kind of changes that occur at this point in my life, and how my thoughts on reading change as I undergo the changes in my life.

A little while ago, I heard in the news that the average lifespan of Korean women now exceeds that of Japanese women. As we head toward being an aging society, I believe reading will remain an important keyword.