The fourth in an award-winning series of interviews with Korean theater professionals, first published in The Dong-A Ilbo.

“There were many stage design workshops in Gyeonggi Province, so I wasn’t well off, but I’d bought a car. In the late 1980s, I got into a car accident in the jurisdiction of the Jongno Police Station in Seoul. During the police questioning, I said I was a stage designer, and the police officer wrote ‘interior design’. When I corrected him, he said, ‘Hey, it’s all the same.’ Two years later, I got into another accident in the jurisdiction of the same police station. The police officer who filed the report was a different person, but the situation was more or less the same. I told him that I was a stage designer, and he wrote ‘unemployed’. I asked him why he wrote ‘unemployed’ and he said, ‘Hey, a hobby is different from a job.’”

But he now stands unchallenged across all forms of performance art, including plays, musicals, and operas, captivating people with creative sets. In 30 years, he has worked on over 500 performances. Who is this man? He is Park Dongwoo (55). I met him at The Dong-a Ilbo on April 25, 2017.

Thirty years since he made his debut, stage designer Park Dongwoo has worked on over 500 stage performances, including plays, musicals, and operas. When working on original performances, he actively expresses his opinions, and he eagerly reinterprets existing works. He conceptualizes and simplifies stage designs as much as possible. And he asserts that stage designers are “poets, artists, and architects”. Caption by reporter An Cheol-min

School and job—Lost and wandering

It seems that Park was in an off and on relationship with stage design for a long time until he became a stage designer. The following is a short introduction for Park I wrote in the first person, putting together information I gained from this interview as well as other interviews.

“I was born in Cheongsong, North Gyeongsang Province, and attended Jinbo Elementary School. When I was fifth grade, my teacher gave me the role of a general called ‘Hwarang Gwanchang’ in a school play, but I refused and said that I’d like to work on costumes or props. I wanted to be a writer when I attended Daegu Middle School and High School. Novelist Choe In-ho was my idol. So I aspired to become an English major at Yonsei University, just like him. But when I was studying for the college entrance exam for the second year in Seoul, I changed my mind. Every time I took the bus from Seoul Station, I saw the Daewoo Building, and I wanted to become a businessman like Kim Woo-choong, the founder of the Daewoo Group. So I became a business administration major at Yonsei University, like he was. Then I attended the freshman orientation for the Yonsei Theater Art Research Club (YTARC) with a high school friend. I loved the atmosphere of the club, and so I stayed. I had a knack for crafts, so I took charge of stage design and sets. I worked on over 20 performances in college. After I graduated, I worked at Daewoo Electronics for about a year and a half. It wasn’t fun. I wanted to design sets. So I quit and studied stage design in graduate school at Hongik University. My job at Daewoo couldn’t convince me to stay because they didn’t know what stage design was. Once I quit, I now had to make a living somehow. I worked on whatever I could, from creating company logos, advertisement and print design to interior design. Then I met stage director Im Young-woong from Sanwoollim Theatre Company. He commissioned me to design a poster for a performance, and I told him, “I’m better at stage design than poster design.” And he let me design the set for A Room in the Woods. At the time, he’d been looking for a new stage designer after Jang Jong-seon, the stage designer Im had worked with for a long time, passed away unexpectedly. That was 1987. And I became a stage designer.”

Park told me an anecdote about meeting novelist Choe In-ho when Choe’s book Dream Journey to the Peach Blossom Land was turned into a musical. Park told Choe, “You’re my idol” and Choe created a character named Park Dongwoo in the novel The Merchant, which was being serialized at the time.

I asked Park, “Did people compliment you on your stage designs during college?” It takes more than just the love of stage design to quit a stable job at a respectable company, and I assumed that one of the reasons he was able to jump into stage design would be positive reviews of his work. “Yes,” he replied.

Park has created great stage design for plays, but he received rave reviews for taking Korean stage design to the next level for the musicals The Last Empress and Hero, which opened on Broadway. This image is of an encore production of the former at Seoul Arts Center after the American tour in 1997. The stage where Empress Myeongseong, Emperor Gojong, and foreign ambassadors are chatting pleasantly is suddenly lifted to reveal Japanese ronin ninjas conspiring to murder the empress. This two-story stage creates a distinct contrast between the two scenes, heightening the dramatic tension on stage | Acom International

Stage, stage, stage—Running and racing

He was like fish in water.

In 1990, three years after he made his debut, Park received an award for stage design (Lost Epitaph) at the Korea Theater Festival. The next year, he received an award for stage design (Garden Balsam Dye) at the Dong-A Theater Awards, the most prestigious theater awards, and another award for stage design (Sins of This World) at the Korea Theater Festival in the following year.

“I believe that I was able to establish myself as a stage designer rather quickly, thanks to the stage designers of the previous generation, who were not recognized for their work.”

What is your threshold of success or failure?

“It’s gotten better now, but in the past I suffered a lot internally. Sometimes, when I had a performance starting up, I’d get a better idea for the stage design the day before. But those ideas were dreams that could never be realized, since I didn’t have time to rebuild the set. I rarely happens these days. I believe I was able to come all this way because I kept on trying to look for the best way.”

How do you combine your own ideas with the audience’s preferences?

“Since it started, performances are popular arts. They’re not Van Gogh’s paintings. They’re not preserved and evaluated after our deaths but as soon as they’re put on. If I like it, and the audience likes it, that’s the best outcome. So I have to hone my sense of things at the top level at all times.”

I meant to ask about the difference between respecting the audience and accommodating their tastes.

“I don’t really feel the difference. Shakespeare’s plays are Bible for the theater, but they were popular during his time too. He edited and revised his plays based on the reactions of his audiences. So it’s not right to keep his plays exactly the same when we put them on now. Because it’s the audience of today that’s watching. Making the plays superficially interesting is accommodating the audience’s taste, but taking into consideration what the audience enjoys today is respect.”

I’m curious about the process of stage design.

“In the past, stage directors commissioned stage designers, but these days production companies do that. Usually I decide after reading the play, but the stage director I have to work with is more important than the play. If I can work with a director who is likeminded, I give okays without even reading the work.

Then comes conceptualization. I’m at my happiest when I can get an idea of the stage after reading the last page of the play. If that doesn’t happen, I do my own research and study history. Sometimes, though, it’s difficult to land on an idea even after all the research. But in general, it doesn’t take very long for me to develop an idea.

After I finish conceptualizing the stage in my head, then comes the process of communication, where ideas become concrete. I sketch the design, plan things out, create models, and research the necessary materials. Once they are decided, then I send them to workshops to get them made. But before I send them to workshops, I talk to the stage director. Ideally, I like to show the set models at the first reading, when the stage director, actors, and designers get together to read the play.

Then the next step is inspection, where we check if everything is properly made. In construction, design, building, and inspection are divided, but in stage performances, the stage designer inspects everything. Sometimes I go to the workshops often; other times I don’t. Compared to the past, the production technology and artistic senses have gotten better.

Once the set is inspected, we bring them to the theater. Then we check if everything works properly once they are installed, and whether there are any technical variables. This is an important step in creating a higher quality stage set.

It seems that stage design differs a lot depending on the genre.

“Musical sets have many different scenes. About 30 or so for just one or two acts. And it’s important to maintain consistency in all the scenes and ensure smooth transition between the scenes. On the other hand, there aren’t many scenes in operas. But each scene has to be big and grand. Sets also have to work as sound reflecting boards. If things like that aren’t considered, it’s a failure because singers can’t hear themselves. Nowadays, stage design is being divided into specialized areas. There are some stage designers who work on operas 90 percent of the time.

I asked him about the latest trends in stage art.

“It’s changing from paint to light, two dimensional to three dimensional, and background to the general environment. Light refers to videos.”

Park is also educating future stage designers. He served as a professor for 12 years at the Stage Art Academy, which was founded in 1992. In 2002, he became a professor of theater at Chung-Ang University, Anseong Campus, and left the university in 2015. Then he started teaching at the Graduate School of Performing Arts in 2016. Although he teaches different classes every term, he is mainly focusing on teaching stage design for majors, as well as the history of theater and theater space research for nonmajors.

Park also has his own studio (in Seoul). He worked in Hyehwa-dong for seven years from 1993, and moved to Seorae Maeul, where he remained for a decade. Then in 2010, he got a small office in front of Seoul Arts Center.

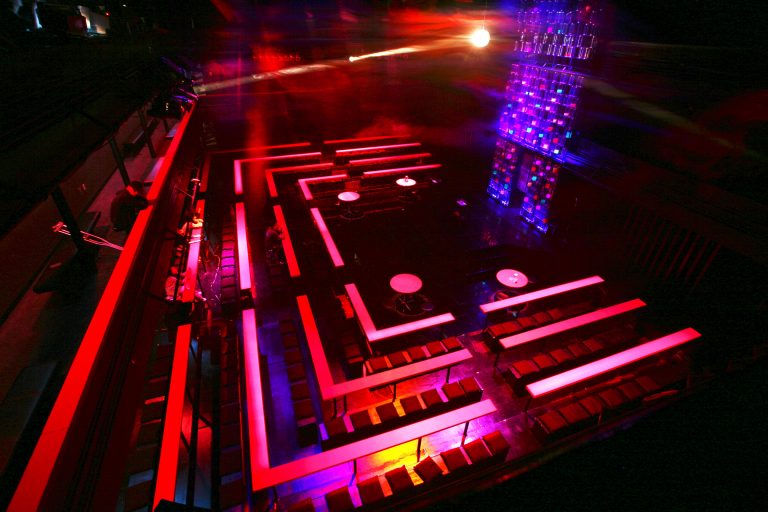

This image is of the seating for Theater Company Elephant Manbo’s Gertrude, which was performed at the Jayu Theater at Seoul Arts Center in 2008. The setting for this play was a bar. Park Dongwoo decorated the entrance of the theater as an entrance to a bar, and the seats like a standing bar. Rather than simply creating the background for the stage, he expanded stage design to create an environment that affects the whole play. In such an environment, even the audience becomes part of the performance | dongwoopark.com

The Last Empress and Hero—Paving the way

Park Dongwoo consistently argues that stage designers are poets, painters, and architects rolled into one. They are poets, because they have to ask a humanistic question of “Why we are putting on this play in this place?” They are painters, because they have to paint pictures on the stage in order to visualize their ideas. And they are architects, because they need to concretize and actually build the pictures that painters created. That is why he always emphasizes the need for stage designers to read the signs of the times and the people. He believes that stage designers should have as much capacity as stage directors and has strived to do that himself.

How does his work come to life specifically?

First, for original plays, he is involved from the scriptwriting process.

“The train scene, which gained attention in the musical Hero, was my idea. The train pulling into the Harbin Station was the highlight. But if the audience sees the train for the first time in that scene, they can’t get a sense of urgency. On top of that they have to process a lot of information at once about how the train came to be at the station. So I thought that we should show the train in Manchu, before the train pulls into Harbin. It was an idea I had in a dream back in middle school. I fell asleep while reading a book about Korean independence activists, and I dreamed that I was one of the activists, who got caught in Manchuria and was being transferred on a train with my hands tied behind my back. When the train was passing over a bridge, I jumped off the train and into the river. Thinking about that dream, I made one of the characters, Sorhui, jump from the train. When I proposed this idea, director Yun Ho-jin readily accepted the idea.”

August 23, 2011, Lincoln Center, New York. The audience exclaimed when the video clip of a train passing through the fields of Manchuria and heading to Harbin Station turned into a real train on stage. (When I asked Park about the technology behind it, he said it was a secret.) Stage and Cinema, an American film and performing arts review site, called the stage, lighting, costume, and special effects designers the “Rembrandts of the theater” and stated that all students studying stage arts need to see it. It was a high praise, comparing the designers and their use of light on stage to Rembrant, the painter of light, and his paintings. The New York Times also remarked that the “highlight is the second act’s life-sized railway car”.

Even before Hero, Park gained confidence from the musical The Last Empress. First opened in Korea in 1995, it was the first Korean original musical to be performed on Broadway in New York in 1997.

Park said, “In preparing and studying to put on the musical in New York, I was able to grow and was finally able to shake off the ‘Broadway complex’.

The ‘Broadway complex’ is the sense of defeat that no matter how much Koreans try, they cannot catch up to the Broadway musicals. Park was immensely shocked when he visited Broadway for two weeks upon receiving the award for stage design from the Korea Theater Festival in 1990. In particular, he was stunned by John Napier’s set design. Napier is a legendary modern set designer along with Josef Svoboda (Czech Republic). Napier is a millionaire set designer who designed the sets for three (Les Miserables, Cats, and Miss Saigon) of the “Big 4”, with the exception of The Phantom of the Opera. In the scene where Javert throws himself into the Seine, Napier pulled up the 20 centimeter-high bridge and spun the stage to create an illusion that Javert was falling into swirling waters of the Seine.

With people like Napier were working in Broadway shows, the local environment did not seem very friendly to the Korean production of The Last Empress. But once on stage, The Last Empress became a masterpiece.

“Everyone agrees that we need to make the shows at the Broadway level of quality. Particularly when bringing Korean musicals overseas. We go to Japan and China frequently. Everyone has that goal in mind, and I’m the same way. Now Broadway is a competitor.”

Second, Park conceptualizes and simplifies.

This is only possible with knowledge of the humanities.

“For the performance of stage director Kim Ara’s Naema, I suggested that we should apply the allegorical narrative method to stage arts and design the main setting as a public bathhouse. The stage director accepted the idea of space that a stage designer proposed. Another example is Gambler, the musical. The original German musical is set in the Peking Palace Casino, but in the Korean version the setting was changed to an Islamic-style casino to create an exotic ambience. In making these changes, the costumes, dialogue, musical instruments, and even the music itself are changed.” (Korean Theater Monthly, June 2003).

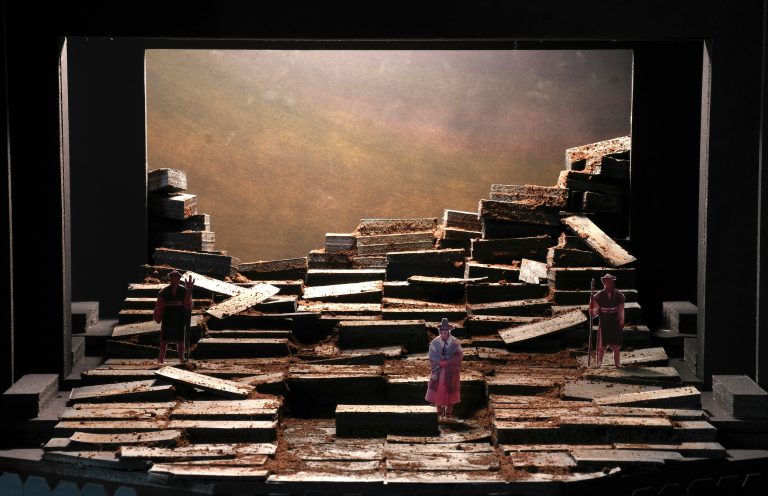

The beginning of Henrik Ibsen’s The Pretenders, performed in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the Seoul Metropolitan Theater. Inga of Varteig, the mother of Haakon is arguing that Haakon is the legitimate heir to the throne by carrying white hot iron with her bare hands, completely unhurt. Park Dongwoo created the stage with three iron walls, never letting the veiled feud, desire, and suspicions escape the stage and creating extreme tension. The huge roots of the tree hanging above the center stage also attracted attention | Seoul Metropolitan Theater

There’s much more.

Orfeo ed Euridice, an opera performed in 2010, is based on a Greek mythology. Park transformed the fairies in the myth into actors wearing hemp mourning clothes, and the grave into a Korean dirt grave. He also used standing screens rather than curtains to switch between scenes. Removing a screen revealed the otherworld, and so on.

In The Pillars of Society performed at LG Art Center in November 2014 the living room of a rich business man into a cabin on a ship and tilted the floor. The set was reminiscent of the Sewol ferry.

“The rehearsals were held in the basement of LG Art Center, and we actually tilted the stage for the rehearsals as well. The actors complained of their legs being sore and feeling as though they were climbing a mountain.”

In Death of a Salesman (directed by Han Tae-sook, performed in the CJ Towol Theater at the Seoul Arts Center) I saw on April 29, 2017, the moving concrete walls that symbolized apartment buildings were impressive. The three huge walls that encompassed the stage gradually begin to close in on the protagonist Willy Loman. The set was designed to visually demonstrate Willy Loman’s alienation, isolation, anxiety, and suffering.

The huge roots hovering above center stage in The Pretenders, which ended its run last month, attracted a lot of attention. It seemed to symbolize the “crown” that the characters in the play craved, or the roots of greed and agony inherent in people, which can’t be controlled.

Regarding good stage design, Park says:

“Good interpretation always comes first, and how the design is bodied out, as well as how the design helps the actors and other elements aside from design are important. And if I add one more, how much the set reflects the stage designer’s personality is important. If a set is designed based solely on historical evidence, the performance would be okay but it’s difficult for it to be great.” (Design Monthly, August 2012).

Then what is Park Dongwoo’s personality? It is conceptualization and simplification.

Early on, he said:

“I was fascinated by the properties of materials and three-dimensional structures, so I focused on scene changes, which were functional and emphasized movement. So instead of filling up the stage, I looked for things to remove from the set. Naturally, simple, abstract, and symbolic aspects come to stand out. In fact, even now, it’s difficult for me to design a bright and cute set. I’d rather design grotesque, cold, and tragic sets.” (Korean Theater Monthly, June 2003).

The above interview was conducted exactly halfway through Park’s stage design career. He spent the first 15 years of his career thinking it, and he hasn’t changed since, other than growing deeper.

Regarding his personality, Park said, “It’s only my disposition and preference. The times I lived through were not pleasant ones. They’re far from being bright or lively. As you know, during my middle school, high school, and college years, when you absorb so much about life, the social atmosphere was despotic.”

Third, he expands background to environment.

Generally, people consider stage design as providing the backdrop for the stage. However, recently, “environment theater” emerged, understanding all external factors that affect the performance as the concept of “environment”. In it, stage design is considered an important player.

Gertrude, a play performed in Jayu Theater at the Seoul Arts Center in 2008, was set in a bar. So Park Dongwoo designed the whole theater from the entrance as a bar, and made the seats like those at a standing bar. It allows the audience to participate in the play as soon as they stepped into the theater. This was an attempt to maximize the theatricality, which cannot be done in films.

At this point, I thought of something uncomfortable. If Park Dongwoo is so good at what he does and so powerful in the field, wouldn’t some directors have difficulty expressing their objections? That would be a huge blow against enhancing the quality of the performance.

“I’m in a cooperative relationship with most stage directors I work with. It’s because people on similar frequencies tend to work together. Of course, there might be a bit of internal conflict due to top-down thinking, Confucian environment, respect for elders, and that kind of culture. Because I’m aware of that, I try not to let things turn out that way. Of course, it doesn’t mean that there’s nothing like that in my relationship with others, but I think that people work with me because I can offer something that offsets that kind of stuff. I doubt people would want to work with me if they’re uncomfortable with me.”

Women Who Stole the Battlefield was performed at the Baek Sung-hee and Chang Man-ho Theater in 2008. The above image is a model of the set. Models are so detailed these days that it is nearly impossible to tell them apart from the actual set. In order to imply that the world we live in exists atop innumerable wars and deaths, Park designed the stage with 200 coffins | dongwoopark.com

30 years on stage—Looking back

This year marks the 30th year since Park became a stage designer.

“I originally thought about putting on an exhibition, but I don’t think I’m prepared for that. I’m planning on writing a book instead of putting on an exhibition. I’d like to write about the complete process of stage design, from text analysis and conceptualization to communication, production, and installation. I plan on emphasizing the conceptualization process. A passive stage designer believes that stage design is giving shape to the ideas that stage directors conceptualize, but I beg to differ.”

He received 17 awards in plays and musicals. In terms of theater performances, he received awards at the Dong-A Theater Awards, Korea Theater Festival, Korea Theater Arts Awards, Seoul Theater Festival, and more. In musicals, he received awards from the Korea Musical Awards, The Musical Awards, Yegreen Musical Awards, and more. The Lee Hae Rang Award he received in 2006 is particularly significant. He was the first stage designer to receive the award, which is generally given to stage directors, actors, theater companies, or playwrights. (In 2015, stage designer Lee Byung-bok received the same award.)

What would you like to tell prospective stage designers?

“It’s an unstable job in the beginning. It’s not a regular job either. But one of the best things is that no one really cares about which college you went to and the entry barrier isn’t high. If you do well in three or four works, people want to work with you. Of course, if you don’t do well in three or four works, then no one would want to work with you, so there’s a big hole in the ground as well.”

He said you have to read a lot to be a good stage designer.

“People these days tend to look for something that other people have already visualized. So you have to read a lot of novels in particular. Reading fiction means that you imagine the next scene, so it helps you train your visual imagination and creativity. To read the signs of the times and society, you have to study broadly, from politics to humanities. If you can’t read the signs, you’ll end up doing what other people have already done before you.”

Park is still young. And so it seems that he still has numerous opportunities to read the signs of the times and society and create more masterpieces.

Have a question for the writer? Send us a mail or sign up for the newsletter.